Oxford University’s Bodleian Library is one of Europe’s oldest libraries and one of the world’s eminent research libraries. Yet, some of its books carry a taint of unscrupulousness given the time of its founding. One of its founding collections is plunder from Portugal in 1596.

Between 1584 and 1604, Protestant England and Catholic Spain fought an intermittent undeclared war sparked by religion and privateering. Portugal, also Catholic, was ruled by and considered part of Spain beginning in 1580. In June 1596, troops led by the second Earl of Essex, Robert Devereux, sailed with a joint English-Dutch fleet. On June 30, the troops captured Cadiz, Spain, and ransacked it.

Devereux’s forces sailed northwest and on July 23 attacked Faro, the capital of the Algarve region of southern Portugal. Meeting little resistance, they quickly controlled the city. Devereux occupied the palace of D. Fernando Martins de Mascarenhas, Bishop of the Algarve. Mascarenhas, a renowned scholar and theologian, had an important private library on theology and canon law. There was little wealth in the town, so the English set it afire and departed on July 27. To avoid leaving empty-handed, Devereux plundered items from the bishop’s library.

Two years later, Thomas Bodley offered to restore the University of Oxford’s library, abandoned a few decades before. In 1600, Devereux gave Bodley 215 volumes, according to Peter Booker of the Algarve History Association. The covers of 91 volumes carried Bishop Mascarenhas’ coat of arms embossed in gold. It’s unknown if they’re the entirety of the bishop’s library, as one other volume and another manuscript are dedicated to the bishop but don’t have his coat of arms, Booker reports. Likewise, some of the library’s books may have belonged to the bishop’s predecessors.

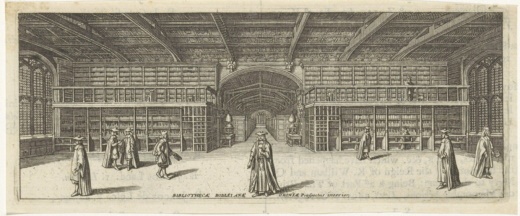

17th-century engraving of Bodleian library interior

That libraries around the world may contain plundered material raises complex issues. “To Essex, Bodley and others in the country, these books would have been seen as a legitimate ‘prize’,” he writes. At the same time, these “displaced or migrated” books raise the question of control of a community’s cultural and political identity.

The view of “Faro 1540,” an association formed to defend and promote Faro’s cultural heritage, is clear. In December 2013, it unanimously approved a motion requesting the return of the books, which it considers historical and cultural treasure. The association sent a formal request and a copy of the motion to the Bodleian Library, Queen Elizabeth II, the British Prime Minister, and the British Embassy in Portugal. The existence or status of any discussions between the association and the library or their respective governments is unknown.

Others ask how the books would have fared were they not in the library. Before Devereux’s literary looting, they were “tormented in a pittifull [sic] manner, [such] that it would grieve a man’s heart to see them,” Thomas James, the Bodleian’s first librarian, recorded. Inquisition censors blotted out what they regarded as heretical sentences and pasted supposedly offensive pages together. Ironically, in July 1616, Mascarenhas became the Inquisitor General of Portugal and compiled a list of authors condemned on religious grounds. Yet today, they are in good shape for their age, on climate-controlled shelves, and accessible to researchers worldwide.

While “ownership” of the books is unresolved, they are safe and secure, Devereux’s fate was worse. The year after donating the books – and before the Bodleian Library opened – he was beheaded for treason.

Libraries and archives were not created or run with the same motivation as those in the modern world, and it is dangerous to draw analogies between these ancient collections and those of today.

Richard Ovenden, Burning the Books: A History of Knowledge Under Attack

(Originally posted at History of Yesterday)