|

|

November 1969 saw the release of a rock album called The Masked Marauders, so named because contractual obligations precluded identifying the world-famous musicians. Still, the liner notes declared it a “once in a lifetime” and “epoch-making” album. It sold more than 100,00 copies. The opening cut, “I Can’t Get No Nookie,” was reportedly called “clearly obscene” by the chair of the Federal Communications Commission. It turns out it was all a hoax.

The first mention of the album came in a review in Rolling Stone magazine’s issue dated October 18, 1969, but on newsstands before then. According to reviewer T.M. Christian, the Masked Marauders were a stunning supergroup: John Lennon, Mick Jagger, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and an unnamed drummer. “It can truly be said that this album is more than a way of life; it is life,” Christian wrote.

The review, though, was concocted by Rolling Stone critic Greil Marcus. Marcus later said he and another writer talked about “how stupid all the then-so-called super session albums were.” So they imagined an ultimate supergroup, and Marcus wrote the fake review under a name taken from Terry Southern’s novel The Magic Christian. After seeing the review, Rolling Stone co-founder and editor Jann Wenner thought it would be a fun spoof for readers.

The review provided plenty of clues that it was satire. Side two of the two-record set, supposedly produced by Al Kooper, opened with “an extremely moving a cappella version of ‘Masters of War,’” by Jagger and McCartney. On side three, Dylan sang “Duke of Earl,” Jagger performed “The Book of Love,” and McCartney contributed “his favorite song, ‘Mammy,’” he wrote. “After the listener has recovered from this string of masterpieces,” side four opened with two songs written for the album, including Jagger’s “new instant classic, ‘I Can’t Get No Nookie.’” It closed with a group vocal of “Oh Happy Day.”

Shortly after the magazine went on sale, Rolling Stone co-founder Ralph Gleason reported it was a hoax. “It was intended as a joke. That’s right, son, a joke,” he wrote in his “On the Town” column in the San Francisco Chronicle. Calling it “simply incredible ANYBODY believed it,” Gleason noted that lots of people were taking it seriously. He was right. There was so much demand for this fake album that Rolling Stone’s November 1, 1969, edition, reported record stores were “swamped with orders.”

The magazine also began to receive plenty of letters about the album. The letters section in the next issue had an editor’s note warning readers not to be misled if they saw an album by that name. The review “was just a laugh. In other words, a fabrication, a hoax, a jest, an indulgence[.]”

Still, Rolling Stone writer Langdon Winner got the Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band to record the songs on the album. Marcus even contributed lyrics to “I Can’t Get No Nookie.” A few songs received some radio airplay, which increased demand for the album. Winner eventually convinced Warner Brothers Records to issue a full-length album, although with one record, not two. It released the album on “Deity Records” to match the review. Warner Brothers announced its “official position” in an in-house memo: “We do not know the names of the people comprising this group and the only thing we know about them is what we read in Rolling Stone.” Still, Rolling Stone writer Langdon Winner got the Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band to record the songs on the album. Marcus even contributed lyrics to “I Can’t Get No Nookie.” A few songs received some radio airplay, which increased demand for the album. Winner eventually convinced Warner Brothers Records to issue a full-length album, although with one record, not two. It released the album on “Deity Records” to match the review. Warner Brothers announced its “official position” in an in-house memo: “We do not know the names of the people comprising this group and the only thing we know about them is what we read in Rolling Stone.”

The week the album was released, Rolling Stone ran a full-page story on how its literally unbelievable review led to an album. “And if people failed to laugh at the Marcus review,” it concluded, “wait ‘til they get ahold of the record itself.”

T.M. Christian returned to write the album’s liner notes, which should have tipped off anyone who read them. Christian “mushed” a dog sled from an air terminal to Igloo Productions to attend the recording sessions. “I Can’t Get No Nookie” was recorded “after an all night party on the tundra with the local Eskimos.” It was named for “the lovely girl friend of Nanook of the North.” Any claims it was obscene “are nothing more than a vile ethnic slur cooked up by some demented mind.” Christian called the music “unmistakably, the sound of the future – the Hudson Bay Sound.”

Despite the hints and disclaimers, The Masked Marauders sold 65,000 copies in two months and more than 100,000 in total. It spent 12 weeks on the Billboard album charts, reaching number 114. On November 29, 1969, “Cow Pie” hit number 123 on the singles charts before disappearing the next week. Many believed they were hearing the purported artists. That didn’t mean the music was good.

“If these boys did do the album, they’ve slipped. It’s terrible,” said an April 3, 1970, review in the Baltimore Sun. Dylan’s rendition of “Season of the Witch,” the writer said, “sounds like Art Carney trying to sound like Bob Dylan doing an imitation of Donovan.” It was, according to the review, the “comedy album of 1969.”

On January 8, 1970, rock critic Robert Christgau called it the “album of the year”– before adding, “I wish I didn’t feel obliged to specify that Marcus intended The Masked Marauders as a parody of rock faddism, especially supergroups and super sessions.” But, he said, the album stood out for having both the world’s worst drum solo and the world’s worst guitar solo.

Playing out the hoax, Deity Records announced the break-up of The Masked Marauders in February 1970. “We don’t need the Marauders,” fictitious label president Solomon Pent-Howes said. “They were nothing until we promoted them and they aren’t really good enough to make it without us.” The end came in April 1971, when Rolling Stone reported Warner Brothers dropped The Masked Marauders from its catalog, relegating any unsold copies to “the drugstore racks.”

The end turned out as imaginary as the band. In 2003, Rhino Records released a limited edition called The Masked Marauders: The Complete Deity Recordings, which has subsequent reissues. In a way, the title continued the hoax. The Masked Marauders is the only Deity Records recording.

What is this anyways? I paid five dollars and eighty-six cents for a record that has Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, John Lennon, and an un-billed drummer — ooh — plus Mick Jagger, and what do I get? This piece of shit!

The Masked Marauders, “Saturday Night at the Cow Palace”

(Originally posted at History of Yesterday)

Nonbookish Linkage

Bookish Linkage

“Patriotism” is [nationalism’s] cult. It should hardly be necessary to say, that by “patriotism” I mean that attitude which puts the own nation above humanity, above the principles of truth and justice.

Erich Fromm, The Sane Society

Not all popes are known for their sanctity. In the Middle Ages, popes routinely acted immorally. But it’s Pope Sylvester II who has the distinction of being the first accused necromancer to rule the church. The claims stemmed from his erudition and religious politics.

Born Gerbert in south-central France around 946, he entered a nearby Benedictine monastery as a child. He excelled in his studies, and in 967, the abbot asked a visiting Spanish count to take Gerbert to Spain to study. He studied at church institutions in Catalonia, a buffer zone between the Franks and the Moors. Although the bishop of Vic guided Gerbert’s education, he still would be exposed to Muslim ideas of mathematics and astronomy inherited from Greece and Persia.

After his three years in Spain, Gerbert became the tutor for Otto II, the son of Holy Roman Emperor Otto I. He then taught at a renowned cathedral school in Reims, France, until 983 when Otto II, now emperor himself, appointed Gerbert the abbot of a monastery in Italy. Otto II died later that year, and Gerbert returned to Reims, where, with some interruptions, he headed the cathedral school until 997. That year he became an advisor to the 16-year-old Holy Roman Emperor Otto III.

Gerbert taught far more than the standard curriculum while at Reims. He built an organ that used water power. He introduced students to Arabic numbers and continued studying the abacus, which he’d learned of in Spain. He even made a mammoth abacus by marking out the floor of the nave of the cathedral and using large disks for the customary beads. He devoted time to astronomy and used spheres and globes in teaching it.

In 998, he was appointed archbishop of Ravenna in Italy. Holy Roman Emperors asserted the power to select the pope and controlled papal elections. On Pope Gregory V’s death in 999, Otto III hand-picked Gerbert to succeed him. Taking the name Sylvester II, he was the first French pope. The assertion of imperial power would lead to the Investiture Controversy, the most significant conflict between secular and religious authority in the 11th century – and the blackening of Sylvester II’s name.

Manuscript illustration of Pope Sylvester II and the Devil (circa 1460) Otto III took control of Rome in 998, built a palace there, and made it the empire’s administrative center. In 1001, Italians revolted against imperial rule, and angry Romans surrounded his palace. He and Sylvester II fled the city in February. Otto III died the following January at age 21. Sylvester II returned to Rome, where he died in May 1003. But the Investiture Controversy blackened his reputation.

The first attacks came from a Cardinal Beno. In a screed against then Pope Gregory VII issued around 1085, Beno said Sylvester II was the first in a line of popes who were sorcerers. He said Gerbert was waited on by demons, who helped him to become pope. Beno reported Gerbert summoned a demon before becoming pope and asked when he would die. The demon said Gerbert wouldn’t die until he said Mass in Jerusalem. One day, Sylvester II said Mass in a church in Rome called the Holy Cross of Jerusalem. “Immediately after, he died a horrid and miserable death, and in between those dying breaths, he begged his hands and tongue (with which, by offering them to demons, he had dishonored God) to be cut to pieces,” Beno wrote in Contra Gregorium VII et Urbanum II (Against Gregory VII and Urban II).

More extensive accusations came from British monk and historian William of Malmesbury in his Gesta Regum Anglorum (Deeds of the Kings of England), written around 1125. He reported that Sylvester II “acquired the art of calling up spirits from hell” when studying in Spain. Moreover, he wrote, Sylvester II resided with a Muslim “philosopher” who sold Sylvester II “his knowledge” and loaned him books. One night Sylvester II stole the one book the man refused to lend. With the book, Sylvester “called up the devil, and made an agreement with him to be under his dominion for ever” if the devil protected him from the man.

William also tells a variation of Benno’s account of Sylvester II’s death. He says Sylvester used the astronomical knowledge he gained in Spain to build a brass or bronze head. He empowered the head to answer “Yes” or “No” to Sylvester II’s questions. When he asked if he would die if he said Mass at Jerusalem, the head said, “No.” He, of course, became ill after saying Mass at the Holy Cross. The pope the cardinals together and “lamented his crimes” at length, William wrote. At that point, Sylvester II “began to rave, and losing his reason through excess of pain, commanded himself to be maimed, and cast forth piecemeal.”

William’s description of the creation of the head manages to equate Sylvester’s II knowledge of astronomy with divination. As the Catholic Church had long condemned fortune-telling, this further proved Sylvester II’s ties to dark powers. Even his tomb supposedly ties him to prophecy. Around 1270, reports circulated that when the sound of rattling bones came from it, it was foretelling the death of the pope. Additionally, at least one historian reports, upon opening the tomb in 1684, Sylvester II’s body was still intact. Upon full exposure to the air, though, it turned to dust, further demonstrating his necromancy.

Modern society considers Sylvester II as a pre-Renaissance humanist and one of his age’s leading mathematicians and scientists. He may prove a saying erroneously attributed to author Arthur C. Clarke: Magic is just science we don’t understand yet.

During Gerbert’s lifetime, science transcended faith and faith encompassed science: The pope studied the stars and found God in numbers.

Nancy Marie Brown, The Abacus and the Cross:

The Story of the Pope Who Brought the Light of Science to the Dark Ages

(Originally posted at Exploring History)

Interesting Reading in the Interweb Tubez

Nonbookish Linkage

- Self-castration in the 16th and 17th centuries linked to romantic disappointment

Bookish Linkage

- Was Bob Dylan the inspiration for Carrie?

The layman’s constitutional view is that what he likes is constitutional and that which he doesn’t like is unconstitutional. That about measures up the constitutional acumen of the average person.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black, Feb. 25, 1971

NOTE: All quotations (sic)

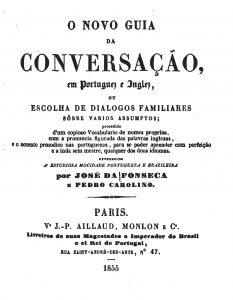

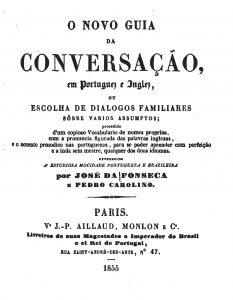

Success comes, some say, when you “find a need and fill it.” In the mid-19th century, Pedro Carlino saw a need for a conversational guide to Portuguese and English. He didn’t let the fact he couldn’t speak English stand in his way. First published in 1855, his book remains available today. Mark Twain called it “perfect.” Its success, though, stems not from usefulness but inadvertent hilarity.

The book’s story actually starts with a different book published nearly 20 years before. A book by Jose da Fonseca intended to help Portuguese speakers with French was published in Paris in 1836. In 1837, a different publisher released Fonseca’s Guide to French and English Conversation. He provided additional material, so the original publisher released a second edition of his Portuguese-French book in 1853. The following year the same publisher issued a book on Portuguese for French speakers by Joseph da Fonseca.

In 1855, that publisher released The New Conversation Guide, in Portuguese and English, listing Jose Fonseca and Carlino as authors. The book is virtually a word-for-word translation of Fonseca’s 1853 second edition. The preface to both books says it uses no “despoiled phrases” and cites the “scrupulous exactness” used in the translations. The truth is the English translations were laughable. In 1855, that publisher released The New Conversation Guide, in Portuguese and English, listing Jose Fonseca and Carlino as authors. The book is virtually a word-for-word translation of Fonseca’s 1853 second edition. The preface to both books says it uses no “despoiled phrases” and cites the “scrupulous exactness” used in the translations. The truth is the English translations were laughable.

Researchers still don’t know who Carlino was and doubt Fonseca had any role in the book since he wrote a French-English book. Given the similarity between the 1853 and 1855 books, they speculate that, whoever he was, Carlino used a Portuguese-to-French dictionary and a French-to-English dictionary to create the book. Simply substituting one word for another doesn’t produce an accurate translation, particularly when it comes to idioms and figures of speech. “Of course, like anything passed through multiple digestive systems the result is a complete mess,” writes Edward Brooke-Hitching in The Madman’s Library.

Misspellings abound but most striking is the ineptitude of the translation. In the vocabulary section, the degrees of “kindred” include the “gossip” and the “gossip wife,” and the tradesmen category includes “Chinaman.” In the animal kingdom, four-footed animals encompass “Shi ass” and “Ass-colt,” while hedgehog, wolf, and snail are on the list of fish and shellfish. Among the phrases it lists:

• Put your confidence at my.

• This girl have a beauty edge.

• Tell me, it can one to know?

• Dry this wine.

• He has spit in my coat.

• He burns one’s self the brains.

• He do the devil at four.

• It must never to laugh of the unhappies.

• Take care to dirt you self.

• Dress my horse.

• Will you fat or slight?

The conversational examples are no improvement. The first thing someone asks a “hair dresser” is, “Your razors, are them well?” While putting his shirt on, a man tells his valet, “Is it no hot, it is too cold yet.” The valet replies, “If you like, I will hot it.” A man tells a dentist he’s hesitant to have a tooth pulled because “that make me many great deal pain.”

Some of the conversations are even a bit alarming. An exchange between two men about riding a horse opens:

–Here is horse who have a bad looks. Give me another; I will not that. He not sall [sic] know to march, he is pursy [sic], he is foundered. Don’t you are ashamed to give me a jade as like? …

–Your Pistols are its loads?

–No; I forgot to buy gun-powder and balls.

Whether as examples or for use, there are also anecdotes, most of which are almost nonsensical. It closes with the aptly named “Idiotisms and Proverbs.” It seems few English speakers ever used any of the following examples.

• The necessity don’t know the low.

• Its are some blu stories.

• With a tongue one go to Roma.

• He is not so devil as he is black.

• Burn the politeness.

• To craunch the marmoset.

• To buy cat in pocket.

Somehow the book drew the attention of various English-language periodicals. Twain said it “has been laughed at, danced upon, and tossed in a blanket by nearly every newspaper and magazine in the English-speaking world.” Unabridged and abridged versions of the book were finally published in London and the United States in 1883 with the title English as She is Spoke.

Loving the book’s “delicious unconscious ridiculousness,” Twain wrote the introduction to one edition, saying it would last as long as the English language. “Whatsoever is perfect in its kind, in literature, is imperishable: nobody can imitate it successfully, nobody can hope to produce its fellow; it is perfect, it must and will stand alone: its immortality is secure,” he wrote.

Twain may not be wrong. Since then, publishers have released at least 16 English-language editions of the book, six since 2004. It’s hard to explain how a wholly inadequate and inaccurate conversational guide is on bookshelves after more than 150 years. Perhaps it’s what Carlino suggested a bookseller might say, “The actual-liking of the public is deprave they does not read who for to amuse one;’s self and but to instruct one’s.”

For that reason we did put, with a scupulous exactness, a great variety own expressions to english and portugese idioms; without to attack us selves (as make some others) almost at a literal translation; translation what only will be for to accustom the portugese pupils, or foreign, to speak very bad any of the mentioned idioms.

Preface, Fonseca’s Guide to French and English Conversation (2d ed.)

(Originally posted at History of Yesterday)

|

Disclaimer

Additionally, some links on this blog go to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. There is no additional cost to you. Contact me You can e-mail me at prairieprogressive at gmaildotcom.

|

Still, Rolling Stone writer Langdon Winner got the Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band to record the songs on the album. Marcus even contributed lyrics to “I Can’t Get No Nookie.” A few songs received some radio airplay, which increased demand for the album. Winner eventually convinced Warner Brothers Records to issue a full-length album, although with one record, not two. It released the album on “Deity Records” to match the review. Warner Brothers announced its “official position” in an in-house memo: “We do not know the names of the people comprising this group and the only thing we know about them is what we read in Rolling Stone.”

Still, Rolling Stone writer Langdon Winner got the Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band to record the songs on the album. Marcus even contributed lyrics to “I Can’t Get No Nookie.” A few songs received some radio airplay, which increased demand for the album. Winner eventually convinced Warner Brothers Records to issue a full-length album, although with one record, not two. It released the album on “Deity Records” to match the review. Warner Brothers announced its “official position” in an in-house memo: “We do not know the names of the people comprising this group and the only thing we know about them is what we read in Rolling Stone.”

In 1855, that publisher released The New Conversation Guide, in Portuguese and English, listing Jose Fonseca and Carlino as authors. The book is virtually a word-for-word translation of Fonseca’s 1853 second edition. The preface to both books says it uses no “despoiled phrases” and cites the “scrupulous exactness” used in the translations. The truth is the English translations were laughable.

In 1855, that publisher released The New Conversation Guide, in Portuguese and English, listing Jose Fonseca and Carlino as authors. The book is virtually a word-for-word translation of Fonseca’s 1853 second edition. The preface to both books says it uses no “despoiled phrases” and cites the “scrupulous exactness” used in the translations. The truth is the English translations were laughable.