|

|

Starting with Gene Autry’s recording of the song “Frosty the Snowman” in 1950, Frosty developed into a pervasive symbol of snowmen in America. Snowmen, though, have a much longer and more noteworthy history.

According to Bob Eckstein, author of The History of the Snowman, the first image of a snowman appears in marginalia in a 1380 manuscript now in the Royal Library of the Netherlands. He says early European snowmen were much more political, “a way for people to say something against their church, or maybe their local politician.” A primary example is the Miracle of 1511 in Brussels.

West-central Europe struggled during the winter of 1510–11, with snow and below-freezing temperatures beginning in mid-November. In some areas, temperatures never got above freezing until a brief mid-February warm-up. Residents of Brussels would even call it the Winter of Death. Starting in January, though, snowmen flourished throughout the city, built by and expressing the views of all levels of its society.

Then part of the Duchy of Brabant in the Habsburg Netherlands, Brussels was governed by aristocrats. One member of each of seven noble families made up the upper council of the city. The city’s many guilds also helped govern but non-bourgeois residents had no political rights. There also was a large wealth gap between the aristocracy and commoners, many of whom lived in considerable poverty.

Snowmen began appearing in the city in January 1511. No one knows if this was a city-organized festival or started by artists hired by the aristocracy. The Miracle of 1511 name and most information about it come from Dutch poet Jan Smeken’s work, “The Miracle of Real or Imaginary Ice and Snow.”

The subjects were wide-ranging. They included representations of Biblical, classical, and mythological figures and creatures from folklore and mythology. And many of the more than 100 snow figures were scatological or pornographic. Smeken’s poem wasn’t illustrated and no contemporary paintings or drawings exist. Smeken, though, didn’t just describe the snow figures. His poem imbues them with human characteristics.

Those who have studied the event suggest the first snowmen dealt with the city’s patricians’ interests. For example, Philip of Burgundy helped build a snowman outside his residence of an artistically proportioned Hercules, who the Burgundians claimed as an ancestor. According to Eckstein, a snow figure of a virgin with a unicorn in her lap erected in front of the ducal palace was “a political cartoon.” He and other authors consider it a comment on the duke, who would become Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, living in Austria with his aunt instead of Brussels.

Soon, all the city’s socioeconomic classes were building snow figures, sometimes as social commentary. A representation of a castle showing a man hiding near a defecating man was mocking a castle commander who fled when it was under attack, according to Herman Pleij, professor emeritus of Medieval Dutch literature at the University of Amsterdam. Pleij also says some snow figures ridiculed rural life. He points specifically to a cow Smeken said delivered “turds, farts and stinking” and a drunk drowning in his own excrement.

Smeken also describes a snow nun seducing a snowman and a snow couple having sex in front of the city fountain. The city’s red-light district had plenty of sexually-oriented figures. According to Smeken, one depicted:

“a huge plump woman, completely naked, her buttocks like a barrel and her breasts finely formed. A dog was ensconced between her legs, her pudenda covered by a rose[.]”

Smeken’s poem shows the intricacy and artistry of the work that went into many of the snow sculptures. Even if the city didn’t sponsor the event, when some of the figures were vandalized it announced that vandals would be severely punished.

A mid-February thaw brought snowman-building to a halt. The Winter of Death wasn’t through exacting a toll, though. Massive flooding resulted when the large amounts of snow it brought melted in the spring. People took refuge in attics. Mills, bridges, and houses were damaged or destroyed.

Yet, it’s the snowmen, not the destruction, that’s remembered. The number and variety of figures and topics caused what happened in Brussels to be considered more than a simple snow festival. “This highly differentiated background among the snowmen is what makes the Brussels snow festival such a wonderful event,” Pleij wrote in his book The Snowmen of 1511. “During one party, a cultural meeting takes place between all manifesting classes, groups and sections within the city.” Eckstein goes further, saying the Miracle of 1511 “literally changed the society of Brussels, giving the public a voice, shifting the balance of power back to the public, and changing the class system within Brussels forever.”

The display of frozen politicians was the town’s de facto op-ed page.

Bob Eckstein, The History of the Snowman

(Originally posted at History of Yesterday)

You’re moving into a new home, so you hire the skilled artist who decorated your current house to decorate your new home. For whatever reason, you fall behind paying him. Explicit drawings of 16 positions for sexual intercourse are on your walls when you go to see his work.

That’s reportedly the situation Pope Clement VII found in the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace in 1524. But the Vatican drawings would end up in a bestselling pornographic book.

Several years before, Pope Julius II had hired Raphael, the master artist, to redecorate four rooms intended as papal apartments. The project outlasted both the Pope and Raphael. On Raphael’s death in 1520, the largest room remained unfinished. Giulio Romano, one of his assistants and heirs, worked on finishing the frescoes in the Sala di Constantino (“Hall of Constantine”) using Raphael’s sketches.

In 1518, Pope Clement, then a cardinal, hired Raphael to design and decorate a palace he was building outside Rome. Romano also became responsible for that project after Raphael’s death. Pope Clement, a Medici, was a chief advisor to the two popes who succeeded Pope Julius II before being elected to Pope himself in 1523.

As the Sala di Constantino neared completion in 1524, Romano became angry at Clement VII for late payment, according to art historian Lynne Lawner. As a result, he drew the 16 sexual positions on the room’s walls, she wrote in I Modi: The Sixteen Pleasures, An Erotic Album of the Italian Renaissance. Pope Clement did not sanction Romano, who finished Raphael’s frescoes and moved to Mantua, Italy. He would become the only specific Renaissance artist mentioned in a William Shakespeare play, described as “that rare Italian master Giulio Romano” in The Winter’s Tale.

Cropped collection of only surviving fragments of “I Modi” By the early 1500s, books could be printed with illustrations. Sketches of Romano’s drawings ended up in the hands of Marcantonio Raimondi, who pioneered reproducing artwork in print and often collaborated with Raphael. Raimondi published Romano’s 16 sketches in 1524 as I Modi (“The Ways”), creating a Renaissance Kama Sutra. Pope Clement ordered all copies confiscated and destroyed, making it the first book of pornography banned by the Catholic Church. The Pope was so outraged he ordered Raimondi imprisoned for a year. Various appeals to the Pope, including his cousin, Cardinal Ippolito de Medici, and poet Pietro Aretino, led to the printer’s release after a few months.

That did not end I Modi’s story. Aretino wrote 16 Sonetti Lussuriosi (“Lust Sonnets”) to accompany the drawings, leading the Metropolitan Museum of Art to call him “the first modern pornographer.” In addition to explicitly describing the sexual acts, some of the sonnets’ characters were recognizable figures of the time. Raimondi and Aretino published this second edition of I Modi in 1527 and the book also became known as Aretino’s Postures and Sixteen Pleasures. “I know not which was the greater, the offense to the eye from the drawings of Giulio, or the outrage to the ear from the words of Aretino,” art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote in 1568.

Unsurprisingly, Pope Clement again banned the book. This time both printed copies and the original plates were destroyed. Only one complete image and some fragments survive, held by the British Museum. Aretino fled Rome for Venice. Raimondi evidently escaped punishment because he was taken for ransom by Spanish soldiers during the Sack of Rome in May 1527 and left Rome destitute.

Although the original was gone, counterfeit copies or attempted reconstructions continued to appear. One made with woodcuts was printed in Venice around 1550, perhaps because Aretino still lived there. In 1657, All Souls College at Oxford threatened several fellows with expulsion for trying to use the college’s printing press to reproduce the book. Despite, or perhaps because of, the church’s longstanding efforts to hunt down copies, a Renaissance bestseller was born. Romano’s 16 drawings have long disappeared; only Aretino’s sonnets remain.

Given how little of the first two editions of I Modi survived, a 1789 French book is the source of most later versions. Carraci’s Aretino combined Aretino’s sonnets with late 16th century engravings by Italian artist Agostino Carracci. Although purportedly based on Romano’s sketches, Carracci used figures from history and Greek and Roman mythology, making it easier to avoid censorship.

I Modi is an anachronism in today’s proliferation of digital porn. Yet, some may still find some amusement in the Vatican being the source of what is perhaps the first written pornography.

I know it when I see it.

Justice Potter Stewart, Jacobellis v. Ohio (1964)

(First posted at History of Yesterday)

Interesting Reading in the Interweb Tubez

- The Four Horsemen of Fake News (“Only a few years ago, the term ‘fake news’ was comedy routine fodder, a reflection of how surreal our politics have become. It’s not funny now.”)

Nonbookish Linkage

Bookish Linkage

He wasn’t physically impotent. So the impotence must lie in his soul.

Carsten Jensen, We, the Drowned

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) reportedly has one of the most challenging handgun qualification courses in the federal government. It mandates quarterly training firearms training and semiannual firearms qualification to ensure agents “maintain a high level of proficiency in the use and safety” of their weapons. So it would probably be a bit embarrassing if an agent shot himself while demonstrating gun safety to children.

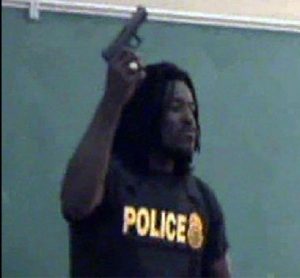

That’s what happened to Lee Paige while making a drug education presentation to about 50 children and parents at a community center in Orlando, Fla., in April 2004. As he talked about the importance of gun safety, he displayed his handgun. “I am the only one in the room professional enough, that I know of, to carry this Glock 40,” he told the group. Almost immediately after, the gun discharged, wounding Paige in the leg. The incident was reported in the press but without identifying Paige.

Even though his wounds were self-inflicted, Paige sued the DEA.

Lee Paige displaying the handgun A parent videotaped his presentation and turned the tape over to the DEA. During the DEA investigation, the tape was copied several times. Ultimately, Paige, a 14 year veteran of the DEA at the time of the incident, was suspended for five days. The videotape was returned to the parent but with the portion with the firearm removed. In March 2005, video of the incident began circulating on the Internet. It also was shown on several television shows, including the Jay Leno Show, CNN Headline News, Fox News, and the Jimmy Kimmel Show.

A year later, Paige sued the DEA. He said he’d become “the target of jokes, derision, ridicule and disparaging comments,” as well as “embarrassing and humiliating comments.” Paige claimed that because the DEA had exclusive custody of the portion of the video in which he shot himself, it was responsible for its disclosure.

Paige’s complaint was dismissed by the federal district court. The U.S. Court of Appeals agreed, although it said the DEA wasn’t blameless. The court said the DEA hadn’t invaded Paige’s privacy because the incident occurred in a public place and he knew a parent was using a video recorder. And while the DEA hadn’t violated the federal Privacy Act, the court said its actions demonstrated the need for federal agencies to safeguard video records “with extreme diligence” in the internet age. “The DEA’s treatment of the video-recording – particularly the creation of so many different versions and copies – undoubtedly increased the likelihood of disclosure and, although [it didn’t violate the law], is far from a model of agency treatment of private data,” it said.

Paige certainly wasn’t the only law enforcement who drew unflattering attention by accidentally shooting themselves in public. But you have to wonder if filing a lawsuit long after the fact minimizes your notoriety.

Speaking personally, you can have my gun, but you’ll take my book when you pry my cold, dead fingers off of the binding.

Stephen King, TIME, June 19, 2000

Between 1879 and 1896, the Rev. William D. Mahan, a minister in the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, issued three editions of previously unknown contemporary accounts of Jesus Christ’s life. There’s virtually unanimous agreement that his work is a fraud, and Mahan’s church suspended him for falsehood and plagiarism. Yet the last version, The Archko Volume, is sold today to readers who praise its historical documents and their importance.

Mahan issued the first work, a 32-page pamphlet called “A Correct Transcript of Pilate’s Court,” in 1879. Its origin story is unusual. Mahan said he met Henry Whydaman, a German, in Missouri in 1856. Whydaman told Mahan of spending five years in Rome and coming across a document called Acta Pilati (“The Acts of Pilate”) in the Vatican library. He said it was an official report from Pontius Pilate to Roman Emperor Tiberius of Christ’s arrest, trial, and crucifixion.

Many called it a fraud. Later investigators also did, including Goodspeed, the author of several books about Apocrypha. He pointed out that, among other things, neither the name of Mahan’s brother-in-law nor the bank he used to transfer money to Whydaman appear in New York City records. Additionally, there was no record of a Father Freelinhusen at the Vatican, and darics were ancient Persian coins not used in the 19th century. In analyzing the content, Goodspeed was blunt: “The whole work is a weak, crude fancy, a jumble of high-sounding but meaningless words, and hardly worth serious criticism.” In 1941, Goodspeed discovered an 1842 pamphlet published in Boston virtually identical to Mahan’s work. That pamphlet, in turn, copied a short story published in Paris in 1837.

The criticism didn’t dissuade Mahan. In 1884 he published The Archaeological and the Historical Writings of the Sanhedrin and Talmuds with nine more previously unknown works joining “Pilate’s Court.” Mahan said they were the result of a 10-year investigation and trips he and two experts made to Rome and Constantinople. The new documents included interviews with “the shepherds and others at Bethlehem” when Jesus was born, an interview with Mary and Joseph (reportedly living in Mecca at the time), and a report from Jewish high priest Caiaphas on the resurrection of Jesus.

The book quickly drew even more fire.

“Pilate’s Court” was some 1,200 words longer than the original pamphlet. Mahan said they reviewed the original in the Vatican library. While it was “more than satisfactory,” he claimed seeing it allowed the expansion of what he’d published. Apparently, the “true copy, word by word” from Father Freelinhusen wasn’t.

Perhaps the most damning evidence came from Rev. James A. Quarles, then president of the Elizabeth Aull Seminary in Missouri and later a philosophy professor at Washington and Lee University. About one-quarter of the book was “Eli’s Story of the Magi,” taken from a parchment Mahan said he found in Constantinople. Quarles established that much of that story was copied verbatim from Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur, published four years earlier. Goodspeed would later observe, “The freedom and extent of Mr. Mahan’s copying of ‘Ben-Hur’ are almost beyond belief.” Quarles also presented evidence indicating Mahan didn’t travel to Rome or Constantinople. Mahan never proved he went nor the existence of the two experts accompanying him.

Mahan’s response was odd. In a November 13, 1884, letter, he told Quarles there were some “misprints” in the book he hoped to revise but stood by its authenticity. Yet he also wrote that the book was:

paying us about 20 dollars [$641.50 today] per day, and its prospects and popularity are increasing every day. You are bound to admit that the items in the book can’t do any harm, even if it were false, but will cause many to read and reflect that otherwise would not. So the balance of good is in its favor.

This good outweighs falsity argument didn’t impress the New Lebanon Presbytery, which governed Mahan’s ministry. On September 28–29, 1885, the Presbytery heard evidence on four charges against Mahan, including plagiarizing Ben-Hur and not going to Constantinople. The 17 members unanimously agreed that he copied “Eli’s Story,” but a slight majority acquitted him of the travel charge. The Presbytery suspended him for one year, and Mahan promised to no longer sell the book.

Mahan still wasn’t deterred. On September 10, 1886, the Presbytery said the suspension “was more the result of sympathy for him and his family than a desire for rigid administration of the law.” It learned, though, that Mahan continued selling the book and planned to bring out new editions. As a result, the Presbytery suspended him indefinitely or until he complied with the Church’s dictates. Church records contain no evidence of reinstatement.

The Presbytery was right. Several new editions, all without “Eli’s Story,” were published from 1897 to the end of the 19th century. By then, the work was known as The Archko Volume. Some 90 pages containing seven letters “regarding God’s providence to the Jews” written by “Hillel the Third” replaced the Ben-Hur plagiarism. If Hillel the Third existed, the letters indicate he was “writing before he was born” and some 450 years after, according to Richard Lloyd Anderson, a professor of Ancient Scripture at Brigham Young University.

One of the book’s ten documents, a letter from Emperor Constantine requesting 50 copies of the Bible, was authentic. Even then, Mahan ventured into the incredible, claiming he transcribed it from the first page of one of Constantine’s Bibles in Constantinople. The identical letter, though, first appeared in a 4th-century biography of Constantine.

Mahan died in 1906 without proving the original documents existed. He wrote in The Archko Volume that “the time has been too long and the distance to the place where the records are kept is too great for all men to make the examination for themselves.” Apparently, the “Eli’s Story” parchment “evaporated,” Anderson observed, and no one ever found the other documents.

Yet The Archko Volume still lives. At least six editions were published in the U.S. in the last ten years. Moreover, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Books-A-Million, and Walmart all sell new copies online. “The book obviously thrives because it is too easy to confuse what we would like to find with what is authentic,” Anderson said. In the end, Mahan created what may be the Bible hoax that won’t die.

Properly read, the Bible is the most potent force for atheism ever conceived.

Isaac Asimov, Yours, Isaac Asimov: A Life in Letters

(Originally posted at Medium)

|

Disclaimer

Additionally, some links on this blog go to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. There is no additional cost to you. Contact me You can e-mail me at prairieprogressive at gmaildotcom.

|