As with every music, rock music has gone through changes. Some changes are for the good. Others, though, are on the other side of the equation. Thirty-eight years ago, perceived changes for the bad brought about the end of two iconic rock institutions. On June 27, 1971, Bill Graham closed the Fillmore East in New York City. On July 4, 1971, Graham held the last concert at Fillmore West in San Francisco.

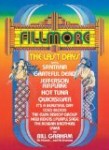

Although Graham would later reopen the Fillmore in San Francisco, this was unquestionably the end of an era. Graham actually started with just The Fillmore, named for its location on Fillmore Street in San Francisco. Graham first had concerts at the venue in 1965 and it became THE scene for the psychedelic and peace and love era. It also helped create a burgeoning art form, the rock poster. Today, they are collector’s items (and a number hang on the walls of my office and home).

Although Graham would later reopen the Fillmore in San Francisco, this was unquestionably the end of an era. Graham actually started with just The Fillmore, named for its location on Fillmore Street in San Francisco. Graham first had concerts at the venue in 1965 and it became THE scene for the psychedelic and peace and love era. It also helped create a burgeoning art form, the rock poster. Today, they are collector’s items (and a number hang on the walls of my office and home).

In 1968, Graham opened an East Cost venue, called, appropriately, the Fillmore East. The first show, on March 8, featured Big Brother & The Holding Company, Tim Buckley and Albert King. Like it’s West Coast counterpart, it became one of the hottest places to hear live music, with appearances by The Doors, Hendrix, The Who, Santana and Led Zeppelin, to name just a handful. In fact, even in the year it was closing it was a huge venue. The Allman Brothers (The Allman Brothers at Fillmore East), Frank Zappa and the Mothers (Fillmore East: June 1971) and the Grateful Dead (Grateful Dead (Skull & Roses)) recorded classic live albums there that year before it closed.

Graham announced the closings in a letter to The Village Voice published on May 6, 1971. Graham said he was closing both venues because the “scene has changed and, in the long run, we are all to one degree or another at fault,” listing seven reasons in particular. Several were personal — lack of a private life, attacks in the press and simply being tired — but others show an astute assessment of the music world and where it was heading.

One problem was with a corporatization of rock music that was resulting in inflated ticket prices. “In 1965 when we began the original Fillmore Auditorium, I associated with and employed ‘musicians.'” he wrote. “Now, more often than not, it’s with ‘officers and stockholders’ in large corporations — only they happen to have long hair and play guitars. I acknowledge their success, but condemn what that success has done to some of them.” A consequence of that change was that for the Fillmores to remain economically viable, “I would be forced to present acts whose musicality fell below my personal expectations and demands.”

Marketing played a role in another respect. Graham wrote, “With all due respect for the role they play in securing work for the artists, the agents have created a new rock game called ‘packaging’; which means simply that if the Fillmore wants a major headliner, then we are often forced to take the second and/or third act that the agent or manager insists upon, whether or not we would take pride in presenting them, and whether or not such an act even belongs on that particular show.”

But Graham was astute enough to realize that the problems weren’t caused just by the industry, musicians or their agents. Audiences, too, were at fault. “In the early days of both Fillmore East and West, the level of audience seemed much higher in terms of musical sophistication.” Graham said. “Now there are too many screams for ‘More’ with total disregard for whether or not there was any musical quality.” And the penultimate paragraphs of his notice were all too prescient:

But whatever has become of [the rock music] scene, wherever it turned into the music industry of festivals, 20,000-seat halls, miserable production quality, and second-rate promoters – however it went wrong – please, each of you, stop and think whether or not you allowed it, whether or not you supported it regardless of how little you received in return.

I am not pleased with this “music industry.” I am disappointed with many of the musicians working in it, and I am shocked at the nature of the millions of people who support that “industry” without asking why. I am not assured that the situation will improve in the future.

So, nearly 40 years later the Fillmores and Graham are unforgettable parts of rock history. But nearly 40 years later, we can still say “amen, brother” to Graham’s insights.

All that I know is that what exists now is not what we started with, and what I see around me now does not seem to be a logical, creative extension of that beginning.

Bill Graham letter to The Village Voice