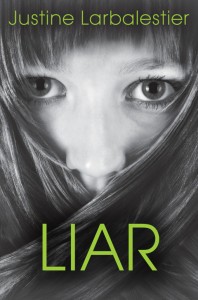

Undoubtedly, we’ve come a long way thanks to the Civil Rights Movement. Yet we can find in sometimes surprising places confirmation that underlying, institutionalized racial issues still exist. A case in point: the picture to the left, which is the cover of the forthcoming young adult novel Liar by Australian author Justine Larbalestier.

Undoubtedly, we’ve come a long way thanks to the Civil Rights Movement. Yet we can find in sometimes surprising places confirmation that underlying, institutionalized racial issues still exist. A case in point: the picture to the left, which is the cover of the forthcoming young adult novel Liar by Australian author Justine Larbalestier.

Quite attractive, isn’t it? Too bad that Micah, the novel’s main character, is “black with nappy hair which she wears natural and short” and could pass for a boy. Now maybe she is a really, really, really excellent liar. Even then, I doubt she can lie her way into looking like the girl on the cover. Larbalestier “strongly objected” to various covers the U.S. publisher, Bloomsbury Books, suggested because “none showed girls who looked remotely like Micah.” As is evident, she lost. And that loss raises a couple issues.

One concern is artistic. Larbalestier says she worked hard to make Micah a believable character. “One of the most upsetting impacts of the cover,” she writes, “is that it’s led readers to question everything about Micah: If she doesn’t look anything like the girl on the cover maybe nothing she says is true. At which point the entire book, and all my hard work, crumbles.” While that is certainly a concern to authors, it is to a great extent mainly an issue between the writer and her publisher.

One concern is artistic. Larbalestier says she worked hard to make Micah a believable character. “One of the most upsetting impacts of the cover,” she writes, “is that it’s led readers to question everything about Micah: If she doesn’t look anything like the girl on the cover maybe nothing she says is true. At which point the entire book, and all my hard work, crumbles.” While that is certainly a concern to authors, it is to a great extent mainly an issue between the writer and her publisher.

More broadly disturbing is what the cover says about our continuing attitudes toward race. Liar is also being published in Australia and the cover of that edition appears at the right. That cover certainly doesn’t create the same artistic concerns. And while I’ll leave it to graphic designers and the like to assess the marketability of the book with the Australian cover, the contrast certainly is an indictment of American attitudes toward race. As Larbalestier wrote on her own blog:

Every year at every publishing house, intentionally and unintentionally, there are white-washed covers. … Editors have told me that their sales departments say black covers don’t sell. Sales reps have told me that many of their accounts won’t take books with black covers. Booksellers have told me that they can’t give away YAs with black covers. Authors have told me that their books with black covers are frequently not shelved in the same part of the library as other YA—they’re exiled to the Urban Fiction section—and many bookshops simply don’t stock them at all. How welcome is a black teen going to feel in the YA section when all the covers are white? Why would she pick up Liar when it has a cover that so explicitly excludes her?

Now maybe what’s really needed is to assess differences among the reading selection of young adults of various races, what might cause them and the extent to which cover art plays a role. And maybe the publisher is simply doing what the marketplace demands. Perhaps Liar would not sell as well in the U.S. without this cover. That’s something we’ll never know. What we do know is that the publishing industry’s perception alone reflects a certain reality of American society. It’s more than a bit depressing that in the 21st century, we still not only judge books by their cover, we judge them by the skin color of the persons on the cover.

Clearly we do not live in a post-racist society.