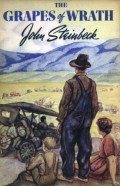

This week marked the 75th anniversary of the publication of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. Normally, what comes to mind is the book’s portrayal of the plight created by the Dust Bowl years of the Depression. Yet it stands for another object lesson about America. It was banned — and burned — in the California county in which the Joads ended their journey.

The Grapes of Wrath was virtually an instant success nationally. It topped the 1939 fiction bestsellers list for both Publisher’s Weekly and the New York Times. It was number eight on the Publisher’s Weekly list the following year. More important, it won the National Book Award and Pulitizer Prize in 1940. In awarding Steinbeck the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1962, the book was described as an “epic chronicle.”

The Grapes of Wrath was virtually an instant success nationally. It topped the 1939 fiction bestsellers list for both Publisher’s Weekly and the New York Times. It was number eight on the Publisher’s Weekly list the following year. More important, it won the National Book Award and Pulitizer Prize in 1940. In awarding Steinbeck the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1962, the book was described as an “epic chronicle.”

It wasn’t well received everywhere, particularly Kern County, Cal. Kern County was among many areas swamped with migrants, straining its resources. At the same time, though, the influx led to the low wages and union busting Steinbeck writes about.

On August 21, 1939, the Kern County Board of Supervisors voted 4-1 to ban the book from the county’s public schools and libraries. Among its reasons: the book had derogatory terms (“Okies”), contained obscenity/profanity, “misrepresented conditions in the county,” and “blamed the local farmers for the plight of the indigent farmers.” According to the resolution, the book “offended our citizenry by falsely implying that many of our fine people are a low, ignorant, profane and blasphemous type living in a vicious, filthy manner.” Bill Camp, a rancher and head of Associated Farmers, a group of local landowners who opposed organized labor, said growers were angry “not because we were attacked but because we were attacked by a book obscene in the extreme sense of the word.”

Wanting to demonstrate just how offended people were, Camp recruited one of his workers, Clell Pruett. Three days after the board’s action, Pruett, standing with Camp and an Associated Farmers board member, lit a copy of the book on fire in a photo op. He then dropped it into a small metal trashcan and the three men watched the book burn. Pruett had not read the novel. He said his action came from a radio story he heard about it.

Wanting to demonstrate just how offended people were, Camp recruited one of his workers, Clell Pruett. Three days after the board’s action, Pruett, standing with Camp and an Associated Farmers board member, lit a copy of the book on fire in a photo op. He then dropped it into a small metal trashcan and the three men watched the book burn. Pruett had not read the novel. He said his action came from a radio story he heard about it.

Not everyone in Kern County supported the ban. County librarian Gretchen Knief wrote the county supervisors asking them to reverse their decision. “It’s such a vicious and dangerous thing to begin,” she wrote. “Besides, banning books is so utterly hopeless and futile. Ideas don’t die because a book is forbidden reading.” The board stood by its vote a week later but, instead of discarding the library’s copies of the books, Knief offered them to other libraries in California. The Grapes of Wrath would remain banned in Kern County until January 1941 — although it supposedly would not be read in the curriculum at East Bakersfield High School in the Kern County School District until 1972 and the ban was not officially overturned by the Board of Supervisors until July 2002.

Sadly, Kern County wasn’t alone. In fact, Kern County’s action appeared to have been inspired by the Kansas City Board of Education removing the book from its schools because of “indecency, obscenity, abhorrence of the portrayal of women and for ‘portraying life in such a bestial way.'” Later, the public library in Buffalo, N.Y., banned it because it used “vulgar words.” In East St. Louis, Ill., meanwhile, the library board voted to burn the book in November 1939 but rescinded the action because of the uproar the vote created. That week, The Grapes of Wrath sold it most copies to that date and the East St. Louis librarian said the book had the longest waiting list in recent years.

As for Pruett, he reportedly read The Grapes of Wrath for the first time some six decades after burning it and said he had no regrets about his actions.

You’re bound to get idears if you go thinkin’ about stuff.

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath