NOTE: All quotations (sic)

Success comes, some say, when you “find a need and fill it.” In the mid-19th century, Pedro Carlino saw a need for a conversational guide to Portuguese and English. He didn’t let the fact he couldn’t speak English stand in his way. First published in 1855, his book remains available today. Mark Twain called it “perfect.” Its success, though, stems not from usefulness but inadvertent hilarity.

The book’s story actually starts with a different book published nearly 20 years before. A book by Jose da Fonseca intended to help Portuguese speakers with French was published in Paris in 1836. In 1837, a different publisher released Fonseca’s Guide to French and English Conversation. He provided additional material, so the original publisher released a second edition of his Portuguese-French book in 1853. The following year the same publisher issued a book on Portuguese for French speakers by Joseph da Fonseca.

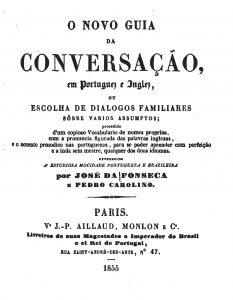

In 1855, that publisher released The New Conversation Guide, in Portuguese and English, listing Jose Fonseca and Carlino as authors. The book is virtually a word-for-word translation of Fonseca’s 1853 second edition. The preface to both books says it uses no “despoiled phrases” and cites the “scrupulous exactness” used in the translations. The truth is the English translations were laughable.

In 1855, that publisher released The New Conversation Guide, in Portuguese and English, listing Jose Fonseca and Carlino as authors. The book is virtually a word-for-word translation of Fonseca’s 1853 second edition. The preface to both books says it uses no “despoiled phrases” and cites the “scrupulous exactness” used in the translations. The truth is the English translations were laughable.

Researchers still don’t know who Carlino was and doubt Fonseca had any role in the book since he wrote a French-English book. Given the similarity between the 1853 and 1855 books, they speculate that, whoever he was, Carlino used a Portuguese-to-French dictionary and a French-to-English dictionary to create the book. Simply substituting one word for another doesn’t produce an accurate translation, particularly when it comes to idioms and figures of speech. “Of course, like anything passed through multiple digestive systems the result is a complete mess,” writes Edward Brooke-Hitching in The Madman’s Library.

Misspellings abound but most striking is the ineptitude of the translation. In the vocabulary section, the degrees of “kindred” include the “gossip” and the “gossip wife,” and the tradesmen category includes “Chinaman.” In the animal kingdom, four-footed animals encompass “Shi ass” and “Ass-colt,” while hedgehog, wolf, and snail are on the list of fish and shellfish. Among the phrases it lists:

• Put your confidence at my.

• This girl have a beauty edge.

• Tell me, it can one to know?

• Dry this wine.

• He has spit in my coat.

• He burns one’s self the brains.

• He do the devil at four.

• It must never to laugh of the unhappies.

• Take care to dirt you self.

• Dress my horse.

• Will you fat or slight?

The conversational examples are no improvement. The first thing someone asks a “hair dresser” is, “Your razors, are them well?” While putting his shirt on, a man tells his valet, “Is it no hot, it is too cold yet.” The valet replies, “If you like, I will hot it.” A man tells a dentist he’s hesitant to have a tooth pulled because “that make me many great deal pain.”

Some of the conversations are even a bit alarming. An exchange between two men about riding a horse opens:

–Here is horse who have a bad looks. Give me another; I will not that. He not sall [sic] know to march, he is pursy [sic], he is foundered. Don’t you are ashamed to give me a jade as like? …

–Your Pistols are its loads?

–No; I forgot to buy gun-powder and balls.

Whether as examples or for use, there are also anecdotes, most of which are almost nonsensical. It closes with the aptly named “Idiotisms and Proverbs.” It seems few English speakers ever used any of the following examples.

• The necessity don’t know the low.

• Its are some blu stories.

• With a tongue one go to Roma.

• He is not so devil as he is black.

• Burn the politeness.

• To craunch the marmoset.

• To buy cat in pocket.

Somehow the book drew the attention of various English-language periodicals. Twain said it “has been laughed at, danced upon, and tossed in a blanket by nearly every newspaper and magazine in the English-speaking world.” Unabridged and abridged versions of the book were finally published in London and the United States in 1883 with the title English as She is Spoke.

Loving the book’s “delicious unconscious ridiculousness,” Twain wrote the introduction to one edition, saying it would last as long as the English language. “Whatsoever is perfect in its kind, in literature, is imperishable: nobody can imitate it successfully, nobody can hope to produce its fellow; it is perfect, it must and will stand alone: its immortality is secure,” he wrote.

Twain may not be wrong. Since then, publishers have released at least 16 English-language editions of the book, six since 2004. It’s hard to explain how a wholly inadequate and inaccurate conversational guide is on bookshelves after more than 150 years. Perhaps it’s what Carlino suggested a bookseller might say, “The actual-liking of the public is deprave they does not read who for to amuse one;’s self and but to instruct one’s.”

For that reason we did put, with a scupulous exactness, a great variety own expressions to english and portugese idioms; without to attack us selves (as make some others) almost at a literal translation; translation what only will be for to accustom the portugese pupils, or foreign, to speak very bad any of the mentioned idioms.

Preface, Fonseca’s Guide to French and English Conversation (2d ed.)

(Originally posted at History of Yesterday)