At least in name, Georg von Trapp achieved international fame as the father of the family portrayed in The Sound of Music musical and film production. How accurate that character was has been challenged by von Trapp’s family. One aspect was right: von Trapp was a retired naval officer. Not only did he serve in the Austro-Hungarian Navy, he was a U-boat commander decorated for his actions in World War I and who rose to the rank of lieutenant commander and the command of a submarine base before the war’s end.

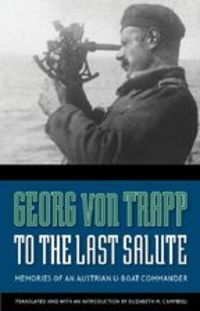

Long before any films or musicals were made about his family, von Trapp wrote a memoir of his World War I service. Originally published in Austria in 1935, it was not translated into English and published in the U.S. until 2007. Translated by a granddaughter, Elizabeth Campbell, To the Last Salute: Memories of an Austrian U-Boat Commander is now out in a paperback edition and provides a rare and intriguing perspective on U-boats in that war.

Long before any films or musicals were made about his family, von Trapp wrote a memoir of his World War I service. Originally published in Austria in 1935, it was not translated into English and published in the U.S. until 2007. Translated by a granddaughter, Elizabeth Campbell, To the Last Salute: Memories of an Austrian U-Boat Commander is now out in a paperback edition and provides a rare and intriguing perspective on U-boats in that war.

Much has been written about Germany’s U-boat campaign in the North Atlantic and the role it played in ultimately bringing the United States into the war. This memoir explores an entirely different aspect of the Triple Alliance’s naval effort. The handful of U-boats in the Austro-Hungarian Navy operated in the Adriatic and Ionian Seas and, less frequently, in the Mediterranean. These were not the U-boats most envision or even what the German Navy had. In fact, when a German U-boat commander visited von Trapp’s boat in 1915, the German officer said, “I would refuse to travel in this crate.”

In addition to being more primitive than the German equipment, when a quicker dive was needed in these U-boats, men would rush to the front of the boat so there would be more weight there. Most, if not close to all, of the sailors slept on the floor, not in berths. The only time the air could be recycled was when the U-boat was on the surface. As a result, the heat and the smell of petroleum and unwashed bodies and clothes would build up to the point it could leave crew members in a stupor, ill and prostrate. Not only did it mean “[e]verything tastes of petroleum,” things got worse in bad weather, when seasickness may strike even the most experienced sailors. In fact, von Trapp writes of one series of squalls endured by the crew of his second U-boat, a captured and converted French submarine. Coming from the conning tower into the interior of the submarine, “takes away your breath,” he wrote, as men confronted “a sickening mixture of oil, cooking odors, and sweat stench.”

Despite the conditions, von Trapp and his crew were successful. In the six months of his first command in 1915, his U-boat sunk three ships, including a French cruiser. Unrestricted U-boat warfare began while von Trapp was commanding his second U-boat. In the course of two and a half years, he and his crew sunk nearly a dozen cargo vessels. In language that reflects the era in which he was writing, he recounts the successful and unsuccessful efforts in some detail, including the tracking of the vessels and trying to evade the torpedo boats and other ships assigned to protect the cargo ships. His recollections also show how strategies, tactics and technology on each side changed as the war progressed.

Yet this isn’t simply a recitation of war feats. As a firsthand account, To the Last Salute also reveals the lives of the crew members and officers of these U-boats and the Austro-Hungarian Navy. We see the experience of having to ration water not only for drinking but for washing the human body. With such restrictions, just wearing clean clothes during a bit of time in port was a pleasure to “prolong and savor.”

While there is also no question of the crews’ patriotism and loyalty to an empire that would dissolve with the end of World War I, von Trapp recognizes the human aspect of what all military men were is doing. In recalling the sinking of the French cruiser, which had more than 700 men aboard, he writes:

So that’s what war looks like! There behind me hundreds of seamen have drowned, men who have done me no harm, men who did their duty as I myself have done, against whom I have nothing personally; with whom, on the contrary, I have felt a bond through sharing the same profession.

In fact, if anything, as the war progressed, any dismay appeared directed toward what was happening on the home front. There is anger toward the Wazachiten, those who not only avoid the front but take advantage of being in the military to obtain items to which the average citizen doesn’t have access. There is frustration in knowing, as von Trapp puts it, that Austrian children “don’t even know what white bread is; they eat turnips.”

Although To the Last Salute covers the point from the mobilization of the Austrian U-boats to the end of the war, reference to direct experience with home is minimal. In fact, although the book refers to various home leave taken by von Trapp, mention of his family or his time with them is almost absent and noticeably lacking in any detail. Perhaps this helped contribute to him later being portrayed as cold and distant from his family. It may, however, simply be that von Trapp simply wanted to portray life from the military aspect and not from a more personal perspective.

In addition, his recounting of conversations contain so many direct quotes that it suggests they are recreated. Yet the fact is that this is a memoir by a military man, not a historian’s account. As such, it focuses on the things and compatriots that were important to him. More important, it provides a rare insider’s view of an aspect of World War I of which we in the West know little to nothing.

In peacetime…it must be like being in a fairy-tale land.

Georg von Trapp, To the Last Salute