Mention Russian literature and most people think of two things. One is the pre-revolution authors whose names are familiar in the West, such as Pushkin, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. The other is the Soviet era, where the government controlled what was published and writers like Boris Pasternak, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Vasily Grossman struggled to have their work published or just to stay free.

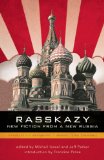

Both periods are over. In fact, Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago is now required reading for Russian students. And while post-Soviet Russia is far from free of censorship, the literature created there today is coming from writers whose work was never subjected to the Soviet literary model. With Rasskazy: New Fiction from a New Russia, Tin House Books seeks to introduce Americans to some of that writing, presenting 22 stories which, with few exceptions, are translated into English for the first time. All are penned by writers whose adult life has been in post-Soviet Russia.

Both periods are over. In fact, Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago is now required reading for Russian students. And while post-Soviet Russia is far from free of censorship, the literature created there today is coming from writers whose work was never subjected to the Soviet literary model. With Rasskazy: New Fiction from a New Russia, Tin House Books seeks to introduce Americans to some of that writing, presenting 22 stories which, with few exceptions, are translated into English for the first time. All are penned by writers whose adult life has been in post-Soviet Russia.

Often post-Soviet Russian literature is called postmodernist when what is really meant is that it is post-Soviet. There are a few pieces that use devices and approaches some might call postmodern (a concept I not only cannot define but I can feel leaching brain cells whenever I try to figure it out). Rasskazy, though, has such variety of style and approach that something will likely appeal to — or annoy — a wide range of tastes. Thus, for example, the opening piece, “They Talk” by Linor Goralik, consists only of snippets of overheard or imagined conversations. Similarly, Ekaterina Taratuta’s “The Seventh Toast to Snails” is a numbered mélange of largely conversational excerpts dealing with seafaring and relationships. And if you’re a fan of resolution in a short story, there are a few here that will frustrate you.

One fairly common thread in Rasskazy (which translates as “stories”) firmly links it to the lengthy history of Russian literature. The classic Russian literature of writers like Tolstoy often was referred to as critical realism because it looked at the faults in society and human struggle. Under Stalin, the officially sanctioned style was “Socialist realism,” which portrayed a glorified “reality” of a proletarian struggle creating a shining Soviet future. In their introduction, Rasskazy editors Mikhail Iossel and Jeff Parker aptly refer to these stories as “New Russian Realism.” Much more akin to critical realism, the stories often describe modern life in Russia, including not only a sense of independence but also alcoholism, economic struggles and Moscow streets with “casinos with Mercedes-Benz parked outside them.” Even “They Talk” fits this category to some extent, because many of the bits of conversation comment on aspects of modern life.

Two of the strongest stories may also reflect one of the country’s ongoing emotional scars. Both Arkady Babchenko’s “Diesel Stop” and “Why the Sky Doesn’t Fall” by German Sadulaev are autobiographically-based stories dealing with the war in Chechnya. Much like Vietnam long dominated American consciousness, seems to continue to loom over much of the Russian psyche.

Babchenko, whose memoir of his military service in Chechnya was translated into English and released in the U.S. last year, looks at the conflict from the standpoint of a Russian soldier. Borrowing from his own experiences, the “Diesel Stop” tells of soldiers in punitive detention after having gone AWOL. Babchenko’s soldier, however, did not go AWOL but overstayed his leave. By far the longest work in the collection, the story focuses in part on how even though he was trying and wanted to return to fight in Chechnya, his detention lasted longer than the war itself. As such, it reveals both the frustration of the average soldier and the often absurd management of the war.

“Why the Sky Doesn’t Fall” could well be considered a touch of magical realism. Having grown up in in a Chechen village, he tells the story from the standpoint of a Chechen. Like Sadulaev, his narrator now lives in St. Petersburg, where he deals with memories of life in Chechnya during the war. But at the same time, the reality that confronts him in those memories can become fabulized, with dragons taking the place of enemy planes. And there is plenty of ordinary reality also.

“Once my memory was a strawberry field,” Sadulaev’s narrator says. “Now my memory is a minefield.” But this is not just figurative language suggesting bits, pieces and fragments of events explode in his memory. It is also literal. Strawberries grow wild in the forest glades around the narrator’s home village. But both sides mined those areas during the war and no one has maps of the minefields. The strawberries now go unpicked despite the fact even more are growing. “Strawberries grow well in fields watered with thick, rich human blood.”

Similarly, in another scene the bodies of betrayed young Chechen fighters killed by the Russians are simply dumped in the central square.

Mothers, howling, dug their children out from the heap of bodies and carried them home. How could they carry them, weighted down with death, in their thin, wrinkled arms? Well, that’s nothing. That’s another question. Empty, frantic eyes, hearts frozen with grief — how could they now carry their hearts, so large, heavy, useless?

No, life can’t get much more real than when it confronts death.

But if military conflict isn’t of interest, there’s a wide variety of glimpses into modern life. “History” by Roman Senchin takes us with a history professor who stumbles into an opposition rally in 2007, where he is mistaken for a protester and arrested. “Spit” by Kirill Ryabov looks at an individual who seeks to return home in a new and more modern society after being released from the mental institution in which he was incarcerated for a crime. Anna Starobinets gives us a glimpse of a young man struggling with obsessive compulsive disorder in “Rules.” Less than 10 pages long, it is a wonderful example of the power of a short story.

These writings apply traditional and nontraditional approaches in looking at modern Russia’s opportunities and woes and the personal and institutional struggles that arise when democratic principles seek root in a society long unaccustomed to them. Whether you like any one story isn’t the point of collections like this. Works in translation allows us to peer into other cultures and nations through the eyes of those who know them best. Equally as important, as many of the stories in Rasskazy prove, translated fiction can provide what all readers want — engaging, enjoyable reading.

Alya’s mother works in one of those many chain restaurants that objectively and honestly speaking are too expensive for undemanding eaters and have no gastronomical worth for everybody else, but nonetheless fail to suffer from a lack of customers.

Olga Zondberg, “Have Mercy, Your Majesty Fish,” Rasskazy