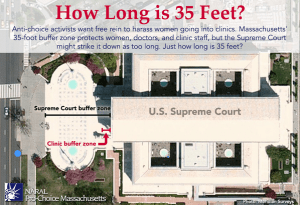

Among the big items in Thursday’s news cycle was the U.S. Supreme Court striking down a Massachusetts law creating a buffer zone around abortion clinics. It didn’t take long for a number of observers to pick up on an unusual perspective on the decision. Federal law makes it illegal to “parade, stand, or move in processions or assemblages in the Supreme Court Building or grounds, or to display … a flag, banner, or device designed or adapted to bring into public notice a party, organization, or movement.” Right now, that’s a 252 by 98 foot buffer zone, compared to a 35-foot radius in the Massachusetts law

Almost any sensible person sees this as ironic. But who says the law has to be sensible? It actually can distinguish the two.

Almost any sensible person sees this as ironic. But who says the law has to be sensible? It actually can distinguish the two.

The Massachusetts statute said no one could “enter or remain” on a “public way or sidewalk” within 35 feet of any portion of an entrance, exit or driveway of an abortion clinic. (It excluded people entering and leaving the clinic, employees, and anyone using the sidewalk or street solely to go someplace other than the clinic.) Among the things that bothered the Supreme Court was that the statute restricted activity on public sidewalks, long recognized as ideal areas for First Amendment activities. Moreover, it didn’t matter what a person in the buffer zone was doing. If, for whatever reason, someone wanted to eat lunch or read a book within the 35 feet, they were breaking the law.

The federal law, 40 U.S.C. § 6135, seems to raise similar questions. In fact, in 1983 the Supreme Court held the statute unconstitutional — when it came to public sidewalks. As a result, subsequent court decisions allowed the statute to apply to the plaza and steps of the Supreme Court building. They reasoned that, unlike public sidewalks, the plaza hasn’t historically been a place for public expression. Thus, the public sidewalk issue key to the Massachusetts decision disappears.

The federal law also can be distinguished because, for example, it doesn’t preclude simply entering and strolling around in the plaza. But that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s constitutional. In fact, last June a federal judge said that even as applied to the plaza the statute violated the Constitution because absolutely bans the activities it covers. In other words, it doesn’t matter why someone might be gathering in the plaza or why a group of people may be parading in it. Just two days later, the Supreme Court adopted a regulation barring “demonstrations” on its grounds that are “reasonably likely to draw a crowd or onlookers.”

That regulation doesn’t change the law itself. The decision invalidating the law is now pending in a federal appeals court. It will be interesting to see if the Supreme Court ultimately ends up hearing the case and, if so, whether it will sense any irony in upholding one law and striking the other.

This clause [precluding assembling or parading on Supreme Court grounds] could apply to, and provide criminal penalties for … even, for example, the familiar line of preschool students from federal agency daycare centers, holding hands with chaperones, parading on the plaza on their first field trip to the Supreme Court.

U.S. District Judge Beryl A. Howell,

Hodge v. Talkin (June 11, 2013)