No one can guess what Melvin Lunda was thinking as he walked to work in downtown Sioux Falls on Thursday, June 20, 1918. Certainly, though, the 28-year-old couldn’t have imagined he would be a domestic fatality of World War I before the day ended. Lunda was what we now call collateral damage brought about by the 1917 Selective Service Act, the country’s first military conscription since the Civil War.

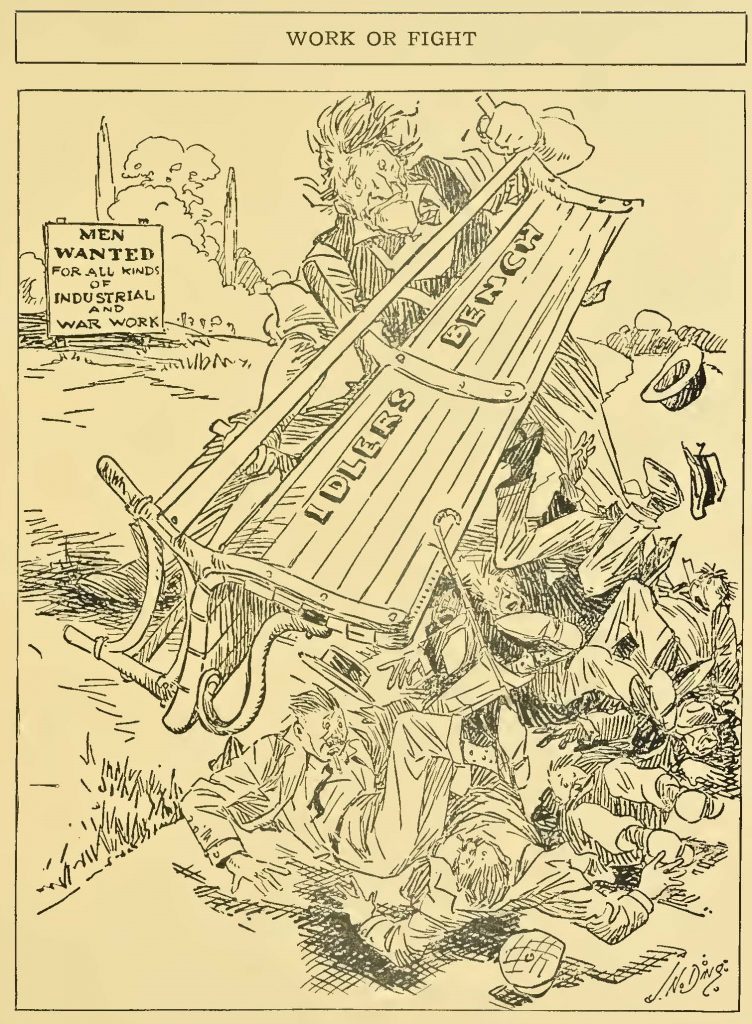

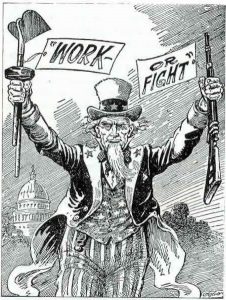

Congress passed the law in May 1917, and a month later, all men between the ages of 21 and 31 were to register with Selective Service. The Act, however, provided exemptions to those employed in industries deemed necessary to maintain the military or “national interest,” including agriculture. Believing too many exemptions were issued, the government issued a “work or fight” order a year later. It required that “idlers,” the unemployed, and any men engaged in “nonproductive occupations and employment” be reported to their local draft board. If determined to be in these categories, the man would lose his exemption and be immediately inducted.

South Dakota actually was ahead of the federal government. In March 1918, the Legislature gave the State Council of Defense the power to press into public service any persons the Council believed were “idle and unemployed.” The Council also was authorized to require registration of “all idle and unemployed citizens or persons.” Anyone failing to do so was subject to a fine of between $5 and $1,000 or 90 days in jail or both.

Although the federal “work or fight” regulations didn’t go into effect until July 1, 1918, authorities in Sioux Falls got a head start. At noon on June 20, 1918, federal and local law enforcement, the county council of defense, and the Home Guard – a state version of the recently federalized National Guard – began combing the city for “idlers.”

Although the federal “work or fight” regulations didn’t go into effect until July 1, 1918, authorities in Sioux Falls got a head start. At noon on June 20, 1918, federal and local law enforcement, the county council of defense, and the Home Guard – a state version of the recently federalized National Guard – began combing the city for “idlers.”

“Methodically, solemnly and systematically the haunts of the unemployed were raided through the city by squads of armed guards,” the Sioux Falls Argus-Leader reported that day. The sweep wasn’t limited to such places; it included businesses and rooming houses. The squads started on the east side of the city and asked men where they were employed, and ordered them to produce their draft registration card. They bundled a suspected “slacker or loafer” off to the city auditorium for a hearing in front of the Minnehaha County Council of Defense. Ultimately some 350 men were rounded up, including some at a dance that night at Wall Lake, but only 11 were held for further investigation.

About 2 p.m., the dragnet reached downtown. “Pool halls, soft drink parlors, every place where men in leisure moments are wont to congregate, were searched and the idle rounded up,” said the Argus-Leader. “Smiles on the faces of those inside, when the guards entered, blanchd [sic] into pallid fear as the arm of the law reached out and the war was brought home to those who imagined they could rest in security.”

Lunda was a mechanic in his brother-in-law’s auto repair shop, located in an alley in the block where the Holiday Inn City Centre now sits. About 4 p.m., a Home Guard private came in and asked Lunda and a co-worker for their registration cards. While the co-worker produced his, Lunda said he’d left his card in the room he rented about four blocks away. He was allowed to go and retrieve it.

Lunda returned about 20 minutes later and collapsed unconscious in front of the Home Guard private. According to the Argus-Leader, before he collapsed Lunda told the private, “I haven’t got my card and now I never will.” The Sioux Falls Journal gave a slightly different version, with Lunda saying, “I never registered – I never will register – now.” The private and a co-worker dragged Lunda outdoors, but he never regained consciousness and died there.

Investigators found an empty vial on the bedroom dresser in Lunda’s North Minnesota Avenue room. They determined that he bought some carbolic acid at a local drug store four days earlier. At some point, Lunda mixed it with potassium cyanide, which mechanics at the time often used to remove rust and clean shining metal parts of cars and trucks. Lunda evidently drank the concoction when he returned to his room on the pretense of retrieving his draft registration card.

Family members said they were unaware Lunda hadn’t registered with the local draft board. His brother-in-law, though, told investigators that Lunda often spoke disparagingly of the war and previously said he would never go to war. Similarly, his boarding house owner said Lunda had a dread of the war and killing, telling her, “I could never kill anybody.” The Argus-Leader concluded Lunda was “[g]ripped by fear and held in in bondage by an unknown terror of the war.” A headline in the Sioux Falls Journal proclaimed: “Apparently Fear Exposure as Slacker Had Death in View When He Went to His Room.”

Family members said they were unaware Lunda hadn’t registered with the local draft board. His brother-in-law, though, told investigators that Lunda often spoke disparagingly of the war and previously said he would never go to war. Similarly, his boarding house owner said Lunda had a dread of the war and killing, telling her, “I could never kill anybody.” The Argus-Leader concluded Lunda was “[g]ripped by fear and held in in bondage by an unknown terror of the war.” A headline in the Sioux Falls Journal proclaimed: “Apparently Fear Exposure as Slacker Had Death in View When He Went to His Room.”

Religion may explain why Lunda failed to register. An unidentified family member said he belonged to the International Bible Students Association, known at the time as “Russellites.” A predecessor of what would become the Jehovah’s Witnesses, Russellites were opposed to fighting in wars. According to a 1917 book by one of its leaders, a book the federal government would label proscribed on the grounds it was antiwar propaganda, “War is in open and utter violation of Christianity.”

Whether Lunda actually was a Russellite is unclear. The week after his death, his parents sent a statement to the press saying he was not a member of the International Bible Students Association. The statement, however, also defended that organization’s tenets and eight of its leaders convicted of conspiracy to defeat the purposes of the Selective Service Act the same day Lunda died. It also said that while Russellites were opposed to suicide and war in general, the Lundas weren’t against the current war. About the same time, a Huron man wrote the Argus-Leader saying Lunda “was in no way associated with” the Russellites. Like the Lundas, he also decried the recent convictions of the organization’s leaders.

Lunda’s suicide didn’t undercut support for “work or fight.” For example, an Argus-Leader article said the dragnet “met with popular favors and was the proper course, particularly as it was fairly conducted.” Meanwhile, the Sioux Falls Journal editorialized that the round-up “was well worth while” and “served a useful purpose.” While recognizing the sweep “was, in effect, martial law for a day and a night,” it “did no one an injustice.”

Even though his death was self-inflicted, Lunda can undoubtedly be considered a casualty of the war. And if he was, in fact, a Russellite, he evidently relied upon the courage of his religious principles. As too often happens, though, both memory and history forgot what happened that June day.

A “just war” – if there could be such a thing – would not require conscription. Volunteers would be plentiful.

Ben Salmon, “An Open Letter to President Wilson”