If the term “variety show” comes up today, it’s most likely in a debate over Jay Leno’s move to prime time television. Otherwise, it brings to mind names like Ed Sullivan, Sonny and Cher or even Donny and Marie, along with whatever smile or cringe they may produce. While variety shows tend to reflect or even contribute to popular culture, few have lasting impact.

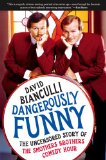

One exception is The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, which aired on CBS from 1967 to 1969. Featuring the comedy duo of Tom and Dick Smothers, the show is most often remembered today for the censorship battles that brought it to a premature end. Yet as longtime TV critic David Bianculli shows in Dangerously Funny: The Uncensored Story of “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour”, the show is just as important for how it helped change television.

One exception is The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, which aired on CBS from 1967 to 1969. Featuring the comedy duo of Tom and Dick Smothers, the show is most often remembered today for the censorship battles that brought it to a premature end. Yet as longtime TV critic David Bianculli shows in Dangerously Funny: The Uncensored Story of “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour”, the show is just as important for how it helped change television.

Dangerously Funny details not only the road Tom and Dick Smothers took to network television, but how the show and its battles with the network evolved. Bianculli makes clear that Tom — the daffy bumbler of the duo — was thoroughly involved in and a driving force behind the television show. Dick — the sensible straight man — left most details to his brother, preferring to spend his time driving race cars and motorcycles.

The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour premiered as a replacement series in the midst of the 1966-67 television season, programmed against NBC’s ratings juggernaut, Bonanza. CBS had eight of the top 10 shows that season, including Green Acres, The Beverly Hillbillies and Gomer Pyle USMC. As a result, Bianculli notes, “all the Smothers Brothers had to do to build a reputation for topical comic commentary was to say anything at all.”

Many of the controversies seem tame today. For example, there was the CBS affiliate that complained of the “extremely poor taste” of a comedy sketch that revolved around Tom Smothers getting a tablecloth caught in his zipper. Or there was a Jackie Mason routine for a March 1969 episode that helped bring the simmering relationship with CBS executives to a boil. CBS refused to air part of it, feeling the comedian discussed sex in a manner not fitting for prime time television. The offensive joke? “I never see a kid play accountant. Even the kids who want to be lawyers play doctor.”

This was an era where Petula Clark caused an uproar by touching Harry Belafonte’s arm during her television special, the first time a man and woman of different races shared physical contact on national television. Americans didn’t have access to dozens or hundreds of channels to watch or record on different television sets in the home. There were only the three national networks and most families watched shows together on the sole set in a household.

But not all the attention focused on whether material was too risqué. Likewise, it didn’t always take years for change to occur. In September 1967, the Smothers Brothers were the first to bring Pete Seeger, blacklisted in the 1950s, back to national television. Because CBS viewed part of Seeger’s “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” as an attack on President Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam policies, it refused to air the song. When Seeger appeared on the show again five months later, he performed it without objection from CBS.

The more material was cut by CBS, the more intractable Tom Smothers became. When a mock sermon by David Steinberg on an October 1968 episode led to a record number of complaints, CBS instituted a first-ever policy of providing affiliates with a closed-circuit telecast of each episode before it aired so local stations could decide if they were going to carry it. By then, the irresistible force of Tom Smothers and the immovable object that was CBS were wholly antithetical.

The ongoing skirmishes culminated in March 1969 when the show brought Steinberg back with another mock sermon. CBS had had enough. Calling Steinberg’s routine “irreverent and offensive” to the audience, it claimed the Smothers Brothers breached their contract by not timely providing a tape of the episode for the closed-circuit telecast to affiliates. It terminated the show. Although the Smothers Brothers would eventually prevail in a lawsuit against CBS, they almost became, like their show, a piece of television history. The Steinberg episode never aired.

Again, though, controversy is not all that marked the show. It won an Emmy in 1968 for comedy writing. (Tom Smothers left his name off the list for fear it would hurt the other writers’ chances. He belatedly was award that Emmy in 2008.) It spanned the entertainment spectrum. In its first season alone, episodes featured Bette Davis and Buffalo Springfield, Jimmy Durante and The Turtles, and Lana Turner and the Electric Prunes. The show helped launch the careers of Glen Campbell, Mason Williams, Pat Paulsen, Steve Martin and Rob Reiner.

The show also was known for having musical guests before their songs hit the charts. Among those appearing on the show were The Doors, Jefferson Airplane, Simon and Garfunkel, and, in a quite notable performance that would leave Pete Townshend with hearing loss, The Who. There was also a guest appearance by George Harrison and the American premiers of the videos of the Beatles performing “Hey Jude” and “Revolution.”

Relying on extensive interviews and research, Bianculli does a fairly good job detailing all these aspects of the show and their relevance and impact. There is, though, a tendency toward repetition and occasionally causing some chronology confusion. It also suffers the inherent inadequacy of the written word to describe performances appreciated best with sight and sound. Still, given how in-depth Bianculli goes, the book is quite readable.

Dangerously Funny leaves little doubt a short-lived variety show altered the face of television. Somewhat ironically, though, while that show seems tame today, there has yet to be another prime time program on the three major television networks doing what it did more than 40 years ago.

What [the Smothers Brothers] managed to say and do was important, and what they were prevented from saying and doing was not less meaningful.

David Bianculli, Dangerously Funny