Sports are replete with stereotypes. Yet few are probably as old and ingrained as that ice hockey goaltenders are quirky weird crazy. Even Hall of Fame goaltender Bernie Parent said, “You don’t have to be crazy to be a goalie. But it helps!” And then there’s the goaltenders who embody the stereotype, such as Gilles Gratton, a goalie who earned the moniker “Gratoony the Loony” (to be distinguished from “loonie,” the $1 Canadian coin).

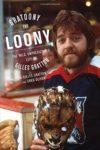

Even though Gratton only played in 47 NHL games in the 1975-76 and 1976-77 seasons, he achieved somewhat legendary status. His autobiography Gratoony the Loony: The Wild, Unpredictable Life of Gilles Gratton, co-written with Greg Oliver, shows how his quirks and actions created the image of the crazy goaltender. But it also tells the story of a French-Canadian boy growing up playing hockey and reaching the big stage while believing there was more to life than a hockey rink.

Gratton spent three seasons in the World Hockey Association, playing in its second All-Star Game, before moving to the NHL. He asserts that he didn’t want to play hockey, “it just seemed that destiny pushed me into it.” Similarly, he says his brother Norm, who would play 201 games with four NHL teams, would rather hunt than play outdoor hockey when they were growing up.

Gratton spent three seasons in the World Hockey Association, playing in its second All-Star Game, before moving to the NHL. He asserts that he didn’t want to play hockey, “it just seemed that destiny pushed me into it.” Similarly, he says his brother Norm, who would play 201 games with four NHL teams, would rather hunt than play outdoor hockey when they were growing up.

The introduction to Gratoony the Loony deals with an event near the end of his career that drew extensive attention. While goalies had fiberglass masks, they were not that far removed from the type made iconic in Friday the 13th. At a home game at Madison Square Garden on January 30, 1977, Gratton came on the ice wearing a mask painted as a snarling lion. (It’s probably apropos that he chose a lion because his astrological sign is Leo.) The mask was so striking that, according to Gratton, the referees and players on the ice came down to look at it. He believes the mask “has come to define me, because most of the rest of my career was just a series of fuck-ups.”

Gratton doesn’t limit his focus to the quirks and antics that he’s remembered for. Instead, Gratoony the Loony is more autobiographical than many sports memoirs. He writes of growing up with parents who were “emotionally absent,” allowing him to do whatever he wanted. He says he struggled with “despair over the meaninglessness of life.” He dropped out of high school after only three days. Before his last NHL season, Gratton no longer wanted to play hockey; he wanted to “meditate, go to ashrams, do my spiritual stuff and uncover life’s secrets.” In fact, after retiring at age 24, Gratton spent several years exploring Transcendental Meditation and yoga, in hopes of becoming “an enlightened being.” Ultimately, though, I think readers would have been better served by a deeper exploration of the effects of how he and his brother (who drank himself to death in 2010) were raised and a more abbreviated discussion of his life after retiring.

Make no mistake. This is a book about hockey. There’s plenty of narrative of Gratton’s years playing hockey, especially professional hockey. In fact, the book at times has the feel of a series of war stories. Perhaps because of that, brief, oral history-like accounts from a wide variety of people are interspersed throughout the book. To me, the inserts tended to break the flow of the book and a number didn’t seem that relevant to the subject at hand. But those interested in the Gratoony the Loony reputation also get what they came for. Among other things, Grattong tells of:

- His mood and thinking being affected by his horoscope and why would you play a goalie who wasn’t in the right mood to perform?

- While playing for Toronto’s WHA team, taking several laps around the practice rink wearing only his mask and skates, ending with a pirouette at center ice.

- When interviewed at center ice in San Diego after being named first star of the game, Gratton told the crowd, “You have a nice city here. It’s too bad you don’t have a good hockey team.”

- After getting hit in the ribs by a puck, telling the doctor the reason it hurt so much was because he was stabbed in the same place by a Spaniard in a prior life.

Plainly, Gratton reinforced the hockey goalie stereotype. He still may be doing so. Gratoony the Loony also tells of his post-hockey astral projection and that he’s currently living two distinct timelines. In the past, he’s lived as a 12th century sailor, a 14th century Indian “hobo,” a 17th century Spanish landowner, an 18th century Spanish priest and a 19th century British surgeon. All in all, to paraphrase Daniel Tosh, it’s not a stereotype if it’s true.

My old enemy had come back to haunt me, and I entered a state where winning and losing did not matter. Nothing seemed important to me

Gilles Gratton, Gratoony the Loony