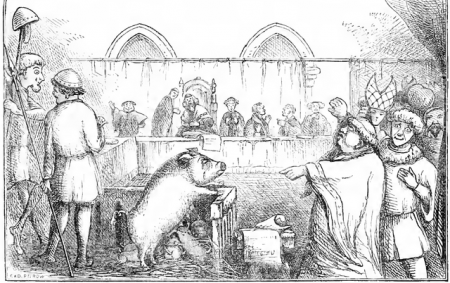

In 1386, a large, diverse crowd gathered in the public square in Falaise, Normandy, France. They were there to witness the execution of a prisoner convicted of murder after mutilating the face and arms of a child. The prisoner wore a new suit of men’s clothes and even the hangman provided himself with a new rope and gloves. In its sentencing, the town tribunal ordered that the prisoner’s head and legs be mangled with a knife before the hanging. In other words, lex talionis, “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” But the criminal wasn’t human. It was a sow, one that unfortunately indulged in eating an infant on the street.

A sow on trial

In 1522, Bartholomew Chassenée was appointed to represent rats charged in Autun, France, with the crime of having eaten the barley crop. He argued that his clients hadn’t properly been served with process by the loudly spoken declaration that they stand trial because all rats, not just those in the village, had to be informed of the charges. An order was then issued that the summons be read from the pulpits of all the parishes in the Autun diocese. When the rats again failed to appear in court, Chassenée bought even more time. He argued that because the rats were widely dispersed, they needed time to prepare to and come to the court.

Chassenée was even more innovative when the rats didn’t appear a third time. This time he said that even though his clients wanted to appear, they would be putting their lives at risk if they tried to come to court. They feared attack by hostile cats — and since the cats belonged to the humans, he asked that cat owners be required to restrain their cats. Evidently weary of the delay and struggles, the plaintiffs didn’t resist the argument and judgment was entered in favor of the rats.

These were far from the only time animals were called to answer to medieval courts. As comical as it may seem today, records indicate animal trials occurred throughout Europe, the majority in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries. One author cites over 200 cases between 824 and 1906, when a dog was sentenced to death in Switzerland for assisting in a murder and robbery.

Nor were these ramshackle affairs. The trials were conducted as if the accused were human. And distinction existed between animals that were in the service of man and those not subject to human control. The former, such as swine, cows, dogs, horses, and sheep, could be arrested, tried, convicted, and executed in secular courts. The latter, such as insects and rodents, fell within the jurisdiction of ecclesiastical courts, which were believed able to expel the defendants and had the power of anathema and excommunication. (Chassenée would even write A Treatise on the Excommunication of Insects.)

Articles about these trials and the theories behind them continue to appear in modern law reviews. So perhaps it can be said that these actions helped form today’s American judicial process.

The judicial prosecution of animals, resulting in their excommunication by the Church or their execution by the hangman, had its origin in the common superstition of the age, which has left such a tragical record of itself in the incredibly absurd and atrocious annals of witchcraft.

E.P. Evans, The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals