There’s a saying a number of people my age share: “If you remember the ’70s, it means you didn’t live through them.” British journalist and author Francis Wheen, though, has me thinking that maybe that lack of memory was not chemically induced but, rather, the result of trying to forget.

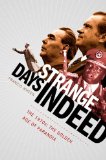

With Strange Days Indeed: The 1970s: The Golden Days of Paranoia, Wheen proposes exactly what the subtitle suggests: that the Seventies were “a pungent mélange of apocalyptic dread and conspiratorial fever.” Paranoia may be a psychiatric term, but given that it is defined as a “pervasive distrust and suspiciousness of others,” there’s plenty of reason the Seventies could be described as the days of paranoia.

With Strange Days Indeed: The 1970s: The Golden Days of Paranoia, Wheen proposes exactly what the subtitle suggests: that the Seventies were “a pungent mélange of apocalyptic dread and conspiratorial fever.” Paranoia may be a psychiatric term, but given that it is defined as a “pervasive distrust and suspiciousness of others,” there’s plenty of reason the Seventies could be described as the days of paranoia.

First published in Britain last year and released in the U.S. this month, Strange Days Indeed kicks off its discussion of the 1970s and paranoia with the poster child, Richard Nixon. Depending on perspective, Nixon can be seen as both cause and effect, with his “enemies list” and taping his own conversations while at the same time burglarizing and bugging those perceived enemies. Wheen, though, doesn’t suggest this was solely an American affliction. He points to how the British government struggled to keep on the lights, declared five states of emergency between June 1970 and February 1974 and actually went to three-day workweeks. Then there was Uganda’s Idi Amin and China in the midst of its Cultural Revolution.

Governments weren’t the only entities displaying the symptoms. There seemed to be a worldwide bloom of so-called revolutionary movements, from Italy’s Red Brigades to Germany’s Baader-Meinhof Gang to America’s Symbionese Liberation Army. Yet many of these groups offered no alternatives to what they opposed. Instead, their terrorism seemed an end rather than a means. “Nihilist hyperbole and exaggerated fury filled the analytical void,” Wheen writes. “It wouldn’t do to admit that they were suffering from little more than existential angst, bourgeois guilt and a nagging discontent at the soullessness and shallowness of consumerist society.”

But politics weren’t the only part of society that seemed to be caught up in a collective derangement. Among those reflecting the tenor of the times was science fiction author Phillip K. Dick. His noted break with reality left him, Wheen says, “trapped in one of his own novels.” For example, Dick wrote numerous letters to the FBI but didn’t mail them. Instead, he put each in an outside trash can, figuring the FBI would get them through its spy operations.

Wheen sometimes tends to overreach a bit in his premise. Certainly, nits could be picked as to whether many of the items he cites are paranoid behavior or symptoms of a widespread anxiety. Additionally, American readers may find a number of British public figures and issues with which they are unfamiliar. And while Wheen’s tour through the Seventies is always tinged with a touch of humor, some readers may want a dictionary handy as they encounter phrases like “corybantic orgy.” Still, Strange Days Indeed has a value not only as history but as a prism on today’s cultural and political psyche.

Wheen’s last book, How Mumbo-Jumbo Conquered the World, used 1979 as a starting point for examining the growth of conspiracy theory, superstition and the supernatural in so-called modern thinking. Looking back on the decade that preceded that survey, he suggests those familiar with the Seventies may see “flickering glimpses of déjà vu” in this century.

He may be right. Plenty of news stories at the end of 2009 suggested the 2000s were the worst decade ever. Time even ran a cover story last December calling it “the Decade from Hell.” This week Newsweek not only suggested America may truly be in decline, it refers to this as “America’s Age of Angst.” Is that angst merely part of a bad flashback or did the golden days of paranoia produce an irreversible effect? Although that question probably can’t be answered for a few decades and is beyond the scope of Strange Days Indeed, Wheen’s look at the Seventies certainly leaves us more to ponder than just that decade.

[T]he Seventies were about as sober as a meths-swilling vagrant waylaying passers-by to tell them that the Archbishop of Canterbury has planted electrodes in his brain.

Francis Wheen, Strange Days Indeed