|

|

For a variety of reasons, I don’t follow or even watch NFL football. I didn’t even watch the last Super Bowl. So I paid no attention to items on the internet about some football player not standing during the national anthem. But a piece on the CBS Evening News Thursday reminded me of the cognitive dissonance of some “patriotic” Americans.

For any who, like me, may not know the background, Colin Kaepernick is a quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers. Although he’d done the same at two prior preseason games, he drew national attention when he sat during the national anthem at a preseason game on August 26. Kaepernick, who is biracial, said after the game, “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color.” During a preseason game in San Diego last night, he was on one knee during the anthem, joined by another teammate.

Naturally, the story blew up with people on both sides. But last night’s game was the Chargers’s annual Salute to the Military night. This, of course, drew more attention. One thing jumped out at me in the CBS story about the game. “If he’s not for our country and the United States flag, get out of my country,” one veteran said on camera. While this clearly hearkens back to the old “love it or leave it” that arose during the Vietnam War, it is most striking that it is a veteran who said it.

We always praise the military and veterans for “defending our freedoms.” Yet a core freedom is the right to protest; it stems from something called the First Amendment. The Supreme Court has long recognized this when it comes to the U.S. flag:

- 1943 — “A person gets from a symbol the meaning he puts into it, and what is one man’s comfort and inspiration is another’s jest and scorn.” (Compulsory pledge of allegiance to flag unconstitutional).

- 1969 — “We have no doubt that the constitutionally guaranteed ‘freedom to be intellectually . . . diverse or even contrary,’ and the ‘right to differ as to things that touch the heart of the existing order,’ encompass the freedom to express publicly one’s opinions about our flag, including those opinions which are defiant or contemptuous.” (Conviction for verbal remarks disparaging the flag unconstitutional).

- 1974 — Displaying an upside down American flag with a peace symbol taped on it, “was not an act of mindless nihilism. Rather, it was a pointed expression of anguish by appellant about the then-current domestic and foreign affairs of his government.”

- 1989 — The unconstitutionality of convicting someone for the expressive act of burning the flag “is a reaffirmation of the principles of freedom and inclusiveness that the flag best reflects, and of the conviction that our toleration of criticism such as [the defendant’s] is a sign and source of our strength.”

- 1990 — “[T]he mere destruction or disfigurement of a particular physical manifestation of the symbol, without more, does not diminish or otherwise affect the symbol itself in any way.” (Holding federal Flag Protection Act unconstitutional.)

People are entitled to announce they are offended by or object to Kaepernick’s actions. They are simply exercising the same right he does. But it is antithetical to claim the NFL or anyone else should punish Kaepernick for his actions because they insult what the flag or military stands for. “Love it or leave it” is fallacious. Americans tend to criticize their country because they want to correct its failings, to see it realize its aspirations. And Kaepernick says his actions came about because “this country stands for freedom, liberty, justice for all. And it’s not happening for all right now.” Seems like he’s trying to champion the same rights veterans and the military seek to protect.

[F]reedom to differ is not limited to things that do not matter much. That would be a mere shadow of freedom. The test of its substance is the right to differ as to things that touch the heart of the existing order.

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624, 642 (1943)

As an initial aside, this post embodies what one can learn learn from just one sentence in a book.

While reading The Romanovs, a nearly 800 page tome on the dynasty that ruled Russia for four centuries, there was a paragraph on page 465 about the head of the Narodnaya Volyaan (“People’s Will”), a terrorist group that assassinated Tsar Alexander II in 1861, being a secret police informant. When the group learned that Sergei Degaev had betrayed it, the only way he could save his life was to kill Georgii Sudeikin, the head of the Tsar’s secret police, to whom Degaev had been reporting. On December 16, 1883, he invited Sudeikin to his apartment where he shot him from behind.

Degaev wanted poster So far, not much more than a brief mention of a relatively incidental historical event. But there was a footnote at the bottom of the page: “Astonishingly, Degaev escaped from Russia and vanished, changing his name to become Alexander Pell, professor of mathematics at the University of South Dakota[.]” (Emphasis added.) Two questions sprang to mind. Is this a misprint? If not, how come I’d never heard of this?

It isn’t a mistake. The USD mathematics professor was indeed Degaev. Somehow, after the assassination, Degaev made it to Paris, where his wife had gone a couple weeks before — on a passport supplied by Sudeikin. The Narodnaya Volyaan expelled him from the movement and barred him from returning to Russia. The latter probably wasn’t much of a penalty. He was being fiercely hunted by Russian authorities, who offered a 10,000 ruble reward (equal to about $200,000 today). Degaev and his wife ended up in St. Louis in 1886. He worked at a chemical plant while she was a laundress and cook. Somewhere along the line they became Alexander and Emma Pell, the names used when they became naturalized citizens in 1891. No one knows why they chose the name Pell.

Pell had earned an engineering degree in Russia. In 1895, he enrolled in a graduate program in mathematics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. He was awarded his doctorate in June 1897. At the time, USD, which held its first classes only 17 years earlier, needed a mathematics professor. By chance, one of Pell’s professors at Johns Hopkins, Lorrain Hulburt, taught at USD from 1887-1891. When USD asked if Hulburt knew of any good candidates, he recommended Pell, although warning of Pell’s “Russian brogue.”

Alexander Pell 1904 Pell began teaching at USD in the fall of 1897 and quickly became popular among the students. In 1901, the student newspaper described him as the “class father” and “Jolly Little Pell.” It’s been reported several times that when a fight broke out between USD students and fans of an opposing team at a football game in Mitchell the following year, Pell waded into the melee to help the outnumbered USD students. While they triumphed, Pell emerged with a torn shirt and bloodied face. When Emma died in 1904, the students dedicated the yearbook to them.

Pell published three academic papers during his first four years at USD but didn’t limit his efforts to mathematics. He urged the school’s board of trustees to start an engineering program. An engineering department was approved in 1903 and opened in 1905. In 1907 the department became the College of Engineering and Pell was its first dean. And while Pell is reported to have said that women didn’t belong in mathematics, he encouraged and supported one of his students, Anna Johnson of Akron, Iowa. After obtaining her USD degree in 1903, Pell helped her pursue graduate studies at the University of Iowa and Radcliffe. In the summer of 1907, Pell traveled to Germany, where Anna was completing a fellowship at the University of Göttingen, and the two were married. She was 24; he was 50.

Pell resigned from USD in 1908, moving to Chicago, where Anna completed her Ph.D. at the University of Chicago. She was the first woman and only the second USD graduate to earn a doctoral degree. She became an extremely well known mathematician. In fact, her biography at a history of mathematics website is longer than his. In 1911, Pell suffered a stroke. She obtained a position at Mount Holyoke College, where they lived until she started teaching at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania in 1918. She ell died in 1921. Anna established a fund for a scholarship at USD and the Dr. Alexander Pell Scholarship is still awarded to mathematics undergrads.

During and after his years at USD, students and faculty were well aware of his work and contributions. Yet they had no clue that “Jolly Little Pell” had been a terrorist assassin. Thus, Degaev/Pell presents an interesting dichotomy. Who was he at heart? Terrorist assassin or respected college professor?

It was not impossible for him to be both. Who wants to be judged solely by certain of their past actions? Moreover, if changes in our lives don’t produce seeming discrepancies then it’s doubtful there’s been real change. Degaev may be a bigger footnote in Russian history than Pell in American history but it’s hard to imagine having experienced such a far-reaching metamorphosis.

Send your Russian mathematician along, brogue and all.

USD wire to Lorrain Hulburt, in Richard Pipes,

The Degaev Affair: Terror and Treason in Tsarist Russia

Paperback books helped create my lifelong reading addiction, in large part because they were affordable. I have fond memories of a small bookstore in an alley behind the Post Office in my hometown. Although the location might suggest a bawdy stock, it was actually akin to the small bookstores we would later see in shopping malls. I would stop in a couple times a month and spend an inordinate amount of time looking through the store, particularly the spinning metal display stands. Paperbacks also had the advantage of fitting in your back pocket for hands-free transportation.

The modern paperback revolution began in Great Britain 81 years ago today when Penguin Books published its first 10 titles. In 1934, a former managing editor at The Bodley Head publishing house in London, Allen Lane, wanted to try publishing more affordable quality literature. His goal was sixpence (about 16 cents U.S. then), the cost of a packet of 10 cigarettes at the time. He and his brothers created the “Penguin Books” imprint and convinced Bodley Head to publish 20,000 copies each of 10 different titles.

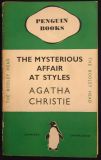

When the book trade placed orders for less than half that initial press run, Lane needed another market. He met with a buyer for Woolworth’s, then the largest chain store in the U.K. He left with an order for 36,000 books and by the end of the summer the chain’s purchases totaled 63,000 copies. Legend has it that the sale occurred because the buyer’s wife happened to walk in on the meeting. She saw Agatha Christie’s The Mysterious Affair at Styles among Lane’s books and told her husband that if books were a sixpence she would buy several a week. When the book trade placed orders for less than half that initial press run, Lane needed another market. He met with a buyer for Woolworth’s, then the largest chain store in the U.K. He left with an order for 36,000 books and by the end of the summer the chain’s purchases totaled 63,000 copies. Legend has it that the sale occurred because the buyer’s wife happened to walk in on the meeting. She saw Agatha Christie’s The Mysterious Affair at Styles among Lane’s books and told her husband that if books were a sixpence she would buy several a week.

Penguin’s sales that year were so good that Allen established Penguin as a separate business in January 1936. By March, Penguin had printed 1 million books and it published its 100th title in June 1937. Much of the initial success was because the first 10 titles were previously published and fairly popular at the time. In order, they were:

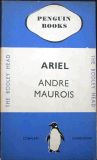

- Ariel, André Maurois

- A Farewell to Arms, Ernest Hemingway

- Poet’s Pub, Eric Linklater

- Madame Claire, Susan Ertz

- The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club, Dorothy L. Sayers

- The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Agatha Christie

- Twenty-five, Beverley Nichols

- William, E.H. Young

- Gone to Earth, Mary Webb

- Carnival, Compton Mackenzie

Penguin’s book covers were basic. They had three horizontal bands, with the upper and lower bands color-coded according to genre. The top band said “Penguin Books,” the middle contained the title and author, and the bottom had a penguin logo. Initially, the cover colors were orange for general fiction, dark blue for biography, and green for crime fiction. As Penguin expanded its subjects, the colors included cerise for travel and adventure, yellow for miscellaneous, red for drama, purple for essays and belles-lettres, and grey for world affairs. Penguin’s book covers were basic. They had three horizontal bands, with the upper and lower bands color-coded according to genre. The top band said “Penguin Books,” the middle contained the title and author, and the bottom had a penguin logo. Initially, the cover colors were orange for general fiction, dark blue for biography, and green for crime fiction. As Penguin expanded its subjects, the colors included cerise for travel and adventure, yellow for miscellaneous, red for drama, purple for essays and belles-lettres, and grey for world affairs.

Lane formed Penguin, Inc. in the U.S. in August 1939. A couple months before, though, Penguin’s success led to the creation of U.S.-based Pocket Books. In June 1939, Pocket published its first 10 titles at only 25 cents each, a tenth the cost of a hardcover book. By 1940, Americans bought 6 million paperback books, which would soar to more than 40 million in 1943. If that weren’t enough to create a nation of readers, between fall 1943 and fall 1947, American publishers gave U.S. soldiers and sailors 123 million paperbacks of 1,322 different titles in compact Armed Services Editions.

Penguin’s and Pocket’s paperbacks not only made book buying cheaper, books became available in grocery stores, drug stores or almost any retail establishment. Paperbacks remain widely available but affordability is again an issue. Today, most paperbacks are issued in trade editions. In 2014, the average price for a fiction trade paperback was $15.52; it was $20.15 for nonfiction. And while mass market paperbacks had an average price of $7.60, the 95 cents I spent for a paperback in 1973 is equivalent to $4.88 today. Keeping book reading strong may well hinge upon the ebook revolution.

We are the people of the book. …. There are teetering piles of books beside the bed and on the floor; there are masses of swollen paperbacks in the bathroom. Our books are us.

Cory Doctorow, “How to Destroy the Book”

(As I’ve been listening to a lot of music during my blog absence, I thought it might be worthwhile trying to resurrect the Midweek Music Moment series.)

I’m one of those people who loved the Beatles (and still do) but was always equivocal when it came to the “who’s your favorite Beatle?” question. But two things eventually cemented George Harrison in that role, both occurring after the Beatles broke up. One was the stellar All Things Must Pass, his 1970 solo album that displayed not only his musicianship but his moralistic world view. The latter was also displayed with the second item, the following year’s Concert for Bangladesh.

The concert was to raise funds the people of Bangladesh, a country that had been wracked by famine, floods and civil war, leaving some 10 million refugees. Harrison managed to bring in such stars as Bob Dylan (who had been basically incognito since 1966), Eric Clapton (who admitted in his autobiography that his physical and mental state was such he has only a “vague memory” of the event), Ringo Starr and Leon Russell. It was the first charity-driven rock concert.

While the concert — actually two shows, one in the afternoon the other in the evening — was held on August 1, 1971, the single, “Bangladesh,” was released in the U.S. 25 years ago today. Here’s Harrison’s more up-tempo performance of the song as an encore at the concert:

The concert version was released as part of the triple album concert recording in December 1971 and part of the concert film releasedMarch 1972. (I still remember going to that film in high school and being mesmerized by it.) The studio single, however, did not appear on an LP until the release of The Best of George Harrison in 1976.

Although I couldn’t feel the pain, I knew I had to try

Now I’m asking all of you

To help us save some lives

George Harrison, “Bangladesh”

It’s been so long since I’ve worked on the blog that you may see occasional burps and oddities. For example, a post scheduled for tomorrow may have already appeared in different form once or twice already.

Additionally, I figured I needed to update both my WordPress installation and the theme to the latest version. I’ve tried to work out the kinks but am not certain that others don’t exist or won’t appear.

It’s hard to be old.

…when the brain is abnormally moist it is necessarily agitated.

Hippocrates, The Medical Works of Hippocrates

|

Disclaimer

Additionally, some links on this blog go to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. There is no additional cost to you. Contact me You can e-mail me at prairieprogressive at gmaildotcom.

|

When the book trade placed orders for less than half that initial press run, Lane needed another market. He met with a buyer for Woolworth’s, then the largest chain store in the U.K. He left with an order for 36,000 books and by the end of the summer the chain’s purchases totaled 63,000 copies. Legend has it that the sale occurred because

When the book trade placed orders for less than half that initial press run, Lane needed another market. He met with a buyer for Woolworth’s, then the largest chain store in the U.K. He left with an order for 36,000 books and by the end of the summer the chain’s purchases totaled 63,000 copies. Legend has it that the sale occurred because  Penguin’s book covers were basic. They had three horizontal bands, with the upper and lower bands color-coded according to genre. The top band said “Penguin Books,” the middle contained the title and author, and the bottom had a

Penguin’s book covers were basic. They had three horizontal bands, with the upper and lower bands color-coded according to genre. The top band said “Penguin Books,” the middle contained the title and author, and the bottom had a