|

|

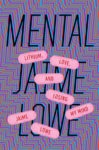

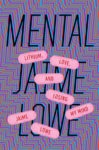

It seems that memoirs about dealing with mental illness are becoming proportionately as ubiquitous as the conditions themselves. Searching “mental health” in Amazon’s biographies and memoirs category produces more than 5,000 results. At least anecdotally, such works coming into the mainstream seems to correspond with increasing public discussion of destigmatizing mental illness. In recounting her 20 years struggling with bipolar disorder in Mental: Lithium, Love, and Losing My Mind, Jaime Lowe not only discusses the condition but examines the treatment of choice.

Bipolar disorder, once known as manic depressive illness, usually first appears between the ages of 15 and 30, with 25 being the average age of onset. Lowe was an overachiever, with her first hospitalization for the condition occurring at age 16. Mental opens with a recounting of her first episode of extreme mania. As with other accounts, one wonders how someone who, to put it colloquially, is “out of their mind can accurately describe what happened. Lowe, though, says that because the experience was “real for me,” she does remember and the incidents leave a feeling that “never fully dissipates.”

While hospitalized, she was started on lithium, the first line treatment for bipolar disorder. What is more striking about this first hospitalization is not necessarily what led to it but the existential state in which she was left once well enough to be released.

Who was I if my actions and thoughts didn’t represent me? What if they did represent me? What if they were extensions of me, rooted in a subconscious realm? What if the me from before I was on lithium is the real me?

Lowe recognizes these questions were too deep for her teenage mind to ponder for long. At the same time, she says, “I no longer had a baseline for reality or even a way to fully trust myself.” And those existential questions, or at least their undercurrent, would not disappear.

Lowe was fortunate because lithium worked for her, allowing her to live and work without being overwhelmed by her condition. In late 1999, Lowe tapered off lithium after having taken it for six years. She began slipping into a manic state even before stopping the drug entirely and once full blown, it would take several months to convince her to go back on the drug. Again, she returned to comparatively normal life. Lowe was fortunate because lithium worked for her, allowing her to live and work without being overwhelmed by her condition. In late 1999, Lowe tapered off lithium after having taken it for six years. She began slipping into a manic state even before stopping the drug entirely and once full blown, it would take several months to convince her to go back on the drug. Again, she returned to comparatively normal life.

Still, her “normality” reflects one of the problems with the psychiatric memoir. As a college student, she lived in Edinburgh, Scotland, for a year studying art history. She’s traveled to Turkey, Germany and Japan and enjoyed the nightlife and other things New York City had to offer while living and working there. To date, the memoir authors largely have been white and relatively privileged. We aren’t hearing the experiences of those, minority or otherwise, who struggle to obtain treatment, let alone those who lack the resources, or the deinstitutionalized. Granted, this is not a problem cause by Lowe. In fact, near the end of Mental, she discusses the fact that while she spent more than $100,000 on outpatient psychiatric care in 18 years in New York City, some 43 million Americans don’t have that option.

In 2014, Lowe encountered something many others who rely on lithium face — kidney damage. Routine blood tests by her primary care physician ultimately revealed that two decades of lithium left her kidneys with only 48 percent function. “I had to choose between my kidneys or losing my sanity,” she writes. Her need to search for a replacement treatment leads her to explore lithium itself. In doing so, Mental is uncommon.

As if infatuated by it, Lowe travels to lithium production sites in Nevada and Bolivia and spas with lithium in the water. She ultimately weaves together concise summaries of the history of treating mental illness, what lithium is, where it comes from and the history of its medical use. And, Lowe says, the nature of lithium creates a problem for patients. Lithium is one of the first three chemical elements created by the Big Bang. That means it can’t be patented so, according to Lowe, there’s no financial incentive to continue studying its effect on the brain. Lowe fortunately found another treatment that has worked, although the book recounts that it was far from a simple process.

As noted, Mental comes from the view of a privileged, white American, which is heightened here by a sense of New York City bohemian cool. Perhaps related to the latter, at times the tone is one of hip casualness and there are occasional clunkers (“temperament itself is so tempestuous”). Lowe also tends to wander or be a bit wordy in the last third of the book, delving into family history and other topics. The flaws, though, do not leave the book or its scope hollow. By going beyond the personal aspects of bipolar disorder, Lowe provides a rare perspective.

I don’t really believe in God, but I believe in lithium.

Jaime Lowe, Mental

Bulletin Board

- Whether hurricane hangover or whatever, there was no Weekend Edition last week as not much struck me as worth passing along. As a result, a couple items below are a week or so old.

Interesting Reading in the Interweb Tubez

Bookish Linkage

Nonbookish Linkage

Here’s a great look at the Adderley Brothers

Frank Zappa is going back on the road — as a hologram

Why Blade Runner is more relevant than ever

The history of corduroy

Merriam-Webster has added more than 250 words and definitions to its dictionary

A visual history of lunchboxes

A brief history of hiding dicks in cartoons

As it is an ancient truth that freedom cannot be legislated into existence, so it is no less obvious that freedom cannot be censored into existence.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, June 24, 1953

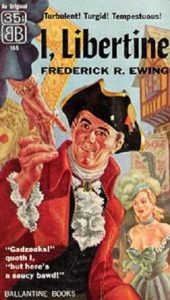

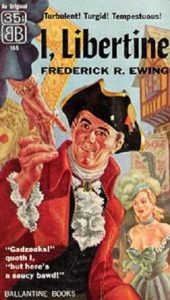

Trump supporters on Reddit last week tried, but failed, to keep Hillary Clinton’s new book from reaching No. 1 on Amazon’s bestseller lists. It wasn’t the first time an effort by a group of people affected the book industry. Perhaps the most interesting one, though, involved demand for a book that didn’t exist.

Jean Shepherd had the graveyard slot on New York City’s WOR radio in the early 1950s. Shepherd frequently offered monologues and commentary on his show. A frequent topic was the difference between “night people,” as he dubbed his listeners, and “day people,” who let their lives be governed by rules, lists and schedules. He found what he considered a prime example of day people and their effect on night people in April 1956.

Shepherd went to a noted New York City bookstore looking for a book with the scripts of an old radio show. The clerk told Shepherd that not only didn’t the store have it, the book didn’t exist because it wasn’t on any publisher’s list. Shepherd, though, knew the book existed and the clerk’s insistence to the contrary led to one of the better book hoaxes.

In telling his audience about his experience, Shepherd suggested they ask bookstores for a book they knew didn’t exist. He and listeners came up with I, Libertine, the first novel in trilogy on 18th century English court life. The imaginary author was Frederick R. Ewing, a retired Royal Navy Commander “well remembered” for a BBC radio series on “Erotica of the 18th Century.” Hundreds of night people responded, asking bookstores and libraries throughout the country for the book. Soon enough, publishers were getting calls from befuddled bookstore clerks and librarians. The nonexistent book was actually banned by the Catholic archdiocese in Boston after a listener who worked for the archdiocese put it on the church’s list of prohibited books as a joke. Once there, evidently no one dared to remove it In telling his audience about his experience, Shepherd suggested they ask bookstores for a book they knew didn’t exist. He and listeners came up with I, Libertine, the first novel in trilogy on 18th century English court life. The imaginary author was Frederick R. Ewing, a retired Royal Navy Commander “well remembered” for a BBC radio series on “Erotica of the 18th Century.” Hundreds of night people responded, asking bookstores and libraries throughout the country for the book. Soon enough, publishers were getting calls from befuddled bookstore clerks and librarians. The nonexistent book was actually banned by the Catholic archdiocese in Boston after a listener who worked for the archdiocese put it on the church’s list of prohibited books as a joke. Once there, evidently no one dared to remove it

Given the number of inquiries publishers were receiving, Ian Ballantine of Ballantine Books investigated and discovered I, Libertine was hokum. He decided to capitalize on it and actually publish a book by that name. He contacted Shepherd and noted SF writer Theodore Sturgeon. Shepherd outlined the story and Sturgeon wrote the book in 30 days. The cover, of course, listed Frederick R. Ewing as the author and called the book “Turbulent! Turgid! Tempestuous!” Shepherd posed for the author photo on the back cover.

I, Libertine was no longer a hoax come September 20, 1956, when it was published with an initial press run of 130,000 copies. The book lost some momentum before it was published, though. On August 1, 1956, the Wall Street Journal ran a front page story detailing the hoax and Ballantine’s plan to publish a book by that name. The media and others felt they had been played for fools, some saying it all was a tawdry publicity stunt. Others, though, suggest the WSJ article actually helped sales.

Today, print copies of the book on Amazon cost from $65 for a paperback to $125 for a hardcover while prices on AbeBooks go as high as $300. Both Amazon and Barnes & Noble offer I, Libertine as an e-book with Sturgeon as the author.

There’s been some who claim I, Libertine hit bestseller lists. I can find no evidence of that — but there’s little doubt that it sold well — for a hoax.

A barrister needs to know the law; abiding by it is quite another specialty.

“Frederick R. Ewing,” I, Libertine

We’ve all watched with fascination those arrangements where hundreds or thousands of dominoes tumble one after the other to form an elaborate illustration. And who hasn’t somewhat envied the person who got to tip the first domino?

Such concepts aren’t limited to fun or entertainment. Images of dominoes falling were crucial to U.S. foreign policy following World War II. In fact, tipping dominoes became a political question, phrased as “Who lost China?” The fears that a communist China meant other Asian nations would, like dominoes, fall under communist control would, in fact, eventually lead America into the Vietnam War.

A number of books have been written about China becoming “Red.” Kevin Peraino, though, makes this a highly readable excursion in A Force So Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949. Peraino’s approach to drawing and keeping the reader in the story of American-Chinese relations in 1949 is by “slipping into the participants’ skins and looking at the dilemmas of 1949 through their eyes.”

Part of America’s problem was that Mao had one objective — to complete the efforts to make China “Red.” As A Force So Swift details, Amerca couldn’t decide on its objective. While a communist China was unanimously seen as detrimental, the well-intentioned but indecisive Harry Truman and U.S. foreign policy were caught up in a variety of factions. Some wanted to continue to support General Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists but even they differed on the nature of that support. Others viewed the Nationalist regime as corrupt and saw supporting it as throwing good money (or military equipment) after bad. Additionally, the government was divided on whether it should attempt to work out accommodations with Mao and whether it should diplomatically recognize a Red China.

The fact thousands of Protestant American missionaries went to China in the first half of the 20th century played a significant role in two ways. First, their reports to their churches reached a large audience, helping create a large ”China lobby” in the U.S. For them, a communist China was anathema. Second, as Peraino shows, Madame Chiang Kai-shek was a far more powerful force in her husband in trying to cultivate and maintain financial and military support for the Nationalists. Her father had traveled to the U.S., where he became an ordained Methodist minister and returned to China to spend a few years as a native missionary. She, in turn, was sent to America at age 15 to be educated, eventually graduating from Wellesley College and becoming thoroughly acculturated to the U.S. The fact thousands of Protestant American missionaries went to China in the first half of the 20th century played a significant role in two ways. First, their reports to their churches reached a large audience, helping create a large ”China lobby” in the U.S. For them, a communist China was anathema. Second, as Peraino shows, Madame Chiang Kai-shek was a far more powerful force in her husband in trying to cultivate and maintain financial and military support for the Nationalists. Her father had traveled to the U.S., where he became an ordained Methodist minister and returned to China to spend a few years as a native missionary. She, in turn, was sent to America at age 15 to be educated, eventually graduating from Wellesley College and becoming thoroughly acculturated to the U.S.

As an indication of her role in efforts to influence American policy, the first chapter opens with her arriving in Washington, D.C., in December 1948. The extent of her clout is evidenced by the fact that she not only visited then-Secretary of State George Marshall on the day she arrived but also a few days later — and both times he was hospitalized for kidney disease. While her husband would withdraw from public view for a lengthy period (by coincidence, the same day Dean Acheson succeeded Marshall in late January 1949), she would remain in the U.S. throughout the year, ultimately unsuccessful in generating support for a continued battle against Mao.

Acheson believed any further U.S. role in supporting the Nationalists was doomed to failure. On the other hand, Louis Johnson, appointed Secretary of Defense in March 1949, argued for continued support for the Nationalists. In addition, Congressional support for the Nationalists was headed by Minnesota Congressman Walter Judd, who’d spent approximately 10 years as a missionary in China. Like others, he argued that if Mao was victorious, other Asian countries would fall to the communists.

Truman, like Acheson, thought a wait-and-see attitude toward China was the best. Part of the State Department’s thinking was that by waiting China and the Soviet Union would come into conflict, reducing political conflict between China and the United States. Ultimately, events outpaced the administration. Not only did Mao take over China and find support from the Soviet Union, Great Britain would recognize Mao’s China.

With an established Red China, Congress wanted to know who, particularly in the State Department, “lost” China to the commies. In the eyes of many policymakers, the first domino had fallen. And in formulating foreign policy no one wanted to be the one who lost the next country.

To court Mao or to confront him? Truman did not want to do either.

Kevin Peraino, A Force So Swift

Want to see how the marketing of a book is affected by who publishes it? Look at Iraq + 100, a collection of stories by 10 Iraqi authors imagining how their country would look 100 years after the 2003 invasion and subsequent occupation by the United States. When originally released in the U.S. last December, the book was subtitled Stories from Another Iraq. Forge, an imprint of noted science fiction publisher Tor Books, has changed the subtitle to The First Anthology of Science Fiction to Have Emerged from Iraq.

That change doesn’t alter the book’s mission, which is perhaps represented by the fact that, having roots in September 11, 2001, the Forge edition is released this week. Rather than wrapping stories around the 2003 invasion, something editor Hassan Blasim did in his own short story collection The Corpse Exhibition, Blasim asked the writers to do something rare for Iraq. As he notes in his introduction to the book, “Iraqi literature suffers from a dire shortage of science fiction writing.” In fact, Blasim was concerned it would be difficult to find writers willing to imagine Iraqi cities 100 years in the future.

Like most anthologies, the end result is mixed. Additionally, Western readers’ perception or appreciation of the book may be affected by the fact seven of the 10 stories were originally written in Arabic and each has a different translator. To the extent this is science fiction, it is “soft” scifi exploring the cultural, political and psychological effects of the invasion and occupation of the country. There’s also a little magical realism and surrealism utilizing Iraq’s and Islam’s history and culture.

Some stories offer optimism. In “The Gardens of Babylon,” Blasim’s own story, while Baghdad is managed by a Chinese corporation, it has become “a paradise for digital technology developers.” Likewise, despite desertification and environmental degradation, this Baghdad is divided into 24 Chinese-designed domes, each a new garden of Babylon. The city exports the world’s best software and extraordinary scientific discoveries. Some stories offer optimism. In “The Gardens of Babylon,” Blasim’s own story, while Baghdad is managed by a Chinese corporation, it has become “a paradise for digital technology developers.” Likewise, despite desertification and environmental degradation, this Baghdad is divided into 24 Chinese-designed domes, each a new garden of Babylon. The city exports the world’s best software and extraordinary scientific discoveries.

Ali Bader imagines a peace-filled future, at least for Iraq. In “The Corporal,” an Iraqi soldier returns to Kut, where he died in the 2003 invasion. “There are no more Sunnis, Shi’as, Christians” in Iraq, he is told, because organized religion is viewed as an impediment to knowing God. The country is long free of conflicts or civil wars. America, however, has become “an extremist state” ruled by religious radicals much like the Taliban governed Afghanistan. In fact, the U.S. is “part of the axis of evil.”

Other futures are far more dystopian. In “Operation Daniel,” Khalid Kaki’s Kirkuk is a wealthy city-state cut off from the rest of Iraq and governed by the Chinese. All languages but Chinese are forbidden and the punishment for anyone speaking or reading in them is being incinerated and “archived” in a synthetic diamond. Diaa Jubaili bases “The Worker” on a statute of that name in Basra. The city exports or has consumed every imaginable resource. It never lacks corpses, whether from disease or starvation. Despite a virtual total collapsed, “the Governor” reassures those still in the city with a monthly address about historical events that surpass the city’s own catastrophes and suffering.

Whether hopeful or despairing, these stories may have Americans ruefully recalling what Gen. Colin Powell reportedly told President George W. Bush before the invasion of Iraq: “You break it, you own it.”

Violence is the most brutal sculptor mankind has ever produced.

Hassan Blasim, “The Gardens of Babylon,” Iraq + 100

|

Disclaimer

Additionally, some links on this blog go to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. There is no additional cost to you. Contact me You can e-mail me at prairieprogressive at gmaildotcom.

|

Lowe was fortunate because lithium worked for her, allowing her to live and work without being overwhelmed by her condition. In late 1999, Lowe tapered off lithium after having taken it for six years. She began slipping into a manic state even before stopping the drug entirely and once full blown, it would take several months to convince her to go back on the drug. Again, she returned to comparatively normal life.

Lowe was fortunate because lithium worked for her, allowing her to live and work without being overwhelmed by her condition. In late 1999, Lowe tapered off lithium after having taken it for six years. She began slipping into a manic state even before stopping the drug entirely and once full blown, it would take several months to convince her to go back on the drug. Again, she returned to comparatively normal life. In telling his audience about his experience, Shepherd suggested they ask bookstores for a book they knew didn’t exist. He and listeners came up with I, Libertine, the first novel in trilogy on 18th century English court life. The imaginary author was Frederick R. Ewing, a retired Royal Navy Commander “well remembered” for a BBC radio series on “Erotica of the 18th Century.” Hundreds of night people responded, asking bookstores and libraries throughout the country for the book. Soon enough, publishers were getting calls from befuddled bookstore clerks and librarians. The nonexistent book was actually banned by the Catholic archdiocese in Boston after a listener who worked for the archdiocese put it on the church’s

In telling his audience about his experience, Shepherd suggested they ask bookstores for a book they knew didn’t exist. He and listeners came up with I, Libertine, the first novel in trilogy on 18th century English court life. The imaginary author was Frederick R. Ewing, a retired Royal Navy Commander “well remembered” for a BBC radio series on “Erotica of the 18th Century.” Hundreds of night people responded, asking bookstores and libraries throughout the country for the book. Soon enough, publishers were getting calls from befuddled bookstore clerks and librarians. The nonexistent book was actually banned by the Catholic archdiocese in Boston after a listener who worked for the archdiocese put it on the church’s