|

|

Do you read the inside flaps that describe a book before or while reading it?

Since I suggested the question, I suppose I have somewhat of an obligation to answer it.

I probably should have been more clear but I’m referring to the flaps on the dust jackets of books. And, as a general rule, I do not read them. I may skim or scan the first paragraph or so in a book I see on the library or bookstore shelves if I’ve never heard of it. That, though, is to just get a general sense of the subject.

If I know I’m going to buy or have a book, I do not read the dust jacket flaps, with the possible exception of the author bio that usually appears at the end of the back inside flap. Particularly with novels, I’ve too often found the descriptions or summaries on the flaps tend to give away information or plot developments I much prefer to discover by reading the book. And it need not be something significant. Regardless of whether it happens on page 2 or page 500, I don’t want to know ahead of time that Character A is going to die. It has not been uncommon for me to read a dust jacket flap after completing the book and being glad I didn’t know something discussed there.

As far as I’m concerned, the flaps are there just to keep the dust jacket in place. Otherwise, they may hamper my imagination of what a particular character will do as the story develops or where the author intends to take the story or a plot line.

I believe in the imagination. What I cannot see is infinitely more important than what I can see.

Duane Michals, Real Dreams

I was so intrigued by Daniel Immerwahr’s creation, The Books of the Century website, that I decided to launch a reading challenge based on it.

Immerwhar has compiled a list for each year of the 20th Century based on

- The top ten bestsellers in fiction, as recorded by Publishers Weekly;

- The top ten bestsellers in nonfiction, also as recorded by Publishers Weekly;

- The main selections of the Book-of-the-Month Club, founded in 1926;

- “Critically acclaimed and historically significant books, as identified by consulting various critics’ and historians’ lists of important books.”

Given the range and breadth of the books covered, I thought this a particularly good opportunity to combine some excellent and classic reading along with a bit of history. Because it is built on bestseller and Book-of-the-Month club lists, I think it tends to reflect American culture at the time. As compiler Immerwahr points out, the lists reflect that “the books we remember today were often not the books that were most popular in the past (in 1925, the year The Great Gatsby was published, the fiction list was topped by A. Hamilton Gibbs’s Soundings).” That’s why I’ve created a Books of the Century Challenge blog to encourage others to participate.

Given the number of books on the lists, this will be an ongoing challenge, not limited to one year. The books read need not be exclusively for the challenge.

At least for the first year, the levels will be:

- Popular Literary Culture 101 — Five books from the entire list.

- Popular Literary Culture 201 — Ten books from the entire list.

- Popular Literary Culture 301 — One book from any of five different decades on the list.

- Popular Literary Culture 401 — One book from each decade on the list.

- Master’s in Popular Literary Culture — Twenty books from the entire list, with at least each decade represented once.

- Doctorate in Popular Literary Culture — Two or more books from each decade on the list.

Although I’m organizing the challenge, I’m not going to start out shooting for a doctorate. My plan is to take the 400 level course, reading a book from each decade on the list. If you’re interested in taking part, head on over to Books of the Century Challenge and sign up with the Mr. Linky in the inaugural post. Participants will be able to post reviews on that blog.

Does there, I wonder, exist a being who has read all, or approximately all, that the person of average culture is supposed to have read, and that not to have read is a social sin? If such a being does exist, surely he is an old, a very old man.

Arnold Bennett, The Journals Of Arnold Bennett

Bulletin Board

- I came across a website yesterday that prompts me to launch a reading challenge and related blog. Full details forthcoming shortly.

Blog Headlines of the Week

Blog Line of the Week

Interesting Reading in the Interweb Tubes

Bookish Linkage

- The Books of the Century compiles by year the top ten bestsellers in fiction and nonfiction, as determined by Publishers Weekly, the main selections of the Book-of-the-Month Club, founded in 1926, and “[c]ritically acclaimed and historically significant books, as identified by consulting various critics’ and historians’ lists of important books.”

- I’m pleased to see that among 45 manly hobbies, “there couldn’t be a manlier hobby” than reading. I must admit, though, that aside from blogging, I am close to a “fail” on the other 44.

- Every Man Dies Alone, my novel of the year choice, is on the longlist for the 2010 Best Translated Book Award. Four others are (horrors!) in my TBR shelves and I’ve been eyeing three others most of last year. I am also currently reading one of the books on the honorable mention list.

- Kirkus Reviews evidently will survive. (Via.)

- Move over, Oprah, and make room for Sam. Sam’s Club is launching a national book club. The first selection is a book I’ve not heard of, Saving CeeCee Honeycutt by Beth Hoffman. (Via.)

- Green Apple Books, my favorite book store in the country, lists its top sellers for 2009.

Nonbookish Linkage

Idleness is fatal only to the mediocre.

Albert Camus, Happy Death

I’ll be honest. Network only recently became one of my favorite films. I saw it shortly after it was released in late 1976 but let some 30 years elapse before watching it over Thanksgiving. When I first saw it, I considered it biting commentary. Now, sadly, I consider it prescient.

Perhaps best known for the phrase, “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it anymore,” Network was a frontal assault on television. The plot is straightforward. Network news anchor Howard Beale (played by Peter Finch) is being let go and, on (or over) the brink of a psychological breakdown, announces he will commit suicide during his last broadcast. Ratings go through the roof and Beale, billed as the “mad prophet,” soon is hosting a nightly “news” program in which he rants and raves and that includes such regulars as Sybil the Soothsayer. Perhaps best known for the phrase, “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it anymore,” Network was a frontal assault on television. The plot is straightforward. Network news anchor Howard Beale (played by Peter Finch) is being let go and, on (or over) the brink of a psychological breakdown, announces he will commit suicide during his last broadcast. Ratings go through the roof and Beale, billed as the “mad prophet,” soon is hosting a nightly “news” program in which he rants and raves and that includes such regulars as Sybil the Soothsayer.

Another plot element gives us a romance between a veteran who helped create television news (William Holden) and a young television executive (Faye Dunaway). His sensibility and caring stands in sharp, almost too blatant, contrast to a woman raised watching television who views and treats life like episodic television.

The movie has a 90 percent rating at Rotten Tomatoes and found plenty of success. Finch and Dunaway won best actor and actress awards at both the Oscars and the Golden Globes while Paddy Chayefsky did the same with the best screenplay award. The movie ranked 66th in the American Film Institute’s 1997 100 Best American Movies and moved up two places in the 2007 edition. The “mad as hell” line also ended up 19th on the AFI’s list of the 100 best movie quotes. In 2000, the film was named to the U.S. National Film Registry by the National Film Preservation Board.

Back in the late ’70s, many of us could identify with not only Network‘s views on television but also the disillusion, cynicism and anger. Fostered in part by Vietnam, Watergate and the oil crisis, we were “mad as hell.” Thus, Howard Beale was really striking a chord when he said, “All I know is, you’ve got to get mad. You’ve got to say, ‘I’m a human being, goddamn it. My life has value.'” For the most part, though, it was film idealism that never really reached fruition. We’re still mad — and mad about many of the same things, war, gas prices, the economy and politicians.

On the television side, Network envisioned a world in which ranting and raving took the place of independent and enterprising journalism, a television network’s entertainment division runs the news department and the any lines remaining between television and reality are blurred at best. Sound familiar? It should. Do names like Howard Stern, Beck or O’Reilly fit that world? How long have we been getting pablum from the “Eyewitless News” teams, both national and local? And the icing on the cake is that the term “reality television,” not only means something, it is a powerhouse.

I remain “mad as hell” about television. That’s why I take Beale’s exhortation to “turn off this goddam [TV] set” to heart. And that’s why watching Network last month makes it a favorite film.

And when the twelfth largest company in the world controls the most awesome goddamned propaganda force in the whole godless world, who knows what shit will be peddled for truth on this network?

Howard Beale (Peter Finch), Network

If the term “variety show” comes up today, it’s most likely in a debate over Jay Leno’s move to prime time television. Otherwise, it brings to mind names like Ed Sullivan, Sonny and Cher or even Donny and Marie, along with whatever smile or cringe they may produce. While variety shows tend to reflect or even contribute to popular culture, few have lasting impact.

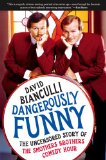

One exception is The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, which aired on CBS from 1967 to 1969. Featuring the comedy duo of Tom and Dick Smothers, the show is most often remembered today for the censorship battles that brought it to a premature end. Yet as longtime TV critic David Bianculli shows in Dangerously Funny: The Uncensored Story of “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour”, the show is just as important for how it helped change television. One exception is The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, which aired on CBS from 1967 to 1969. Featuring the comedy duo of Tom and Dick Smothers, the show is most often remembered today for the censorship battles that brought it to a premature end. Yet as longtime TV critic David Bianculli shows in Dangerously Funny: The Uncensored Story of “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour”, the show is just as important for how it helped change television.

Dangerously Funny details not only the road Tom and Dick Smothers took to network television, but how the show and its battles with the network evolved. Bianculli makes clear that Tom — the daffy bumbler of the duo — was thoroughly involved in and a driving force behind the television show. Dick — the sensible straight man — left most details to his brother, preferring to spend his time driving race cars and motorcycles.

The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour premiered as a replacement series in the midst of the 1966-67 television season, programmed against NBC’s ratings juggernaut, Bonanza. CBS had eight of the top 10 shows that season, including Green Acres, The Beverly Hillbillies and Gomer Pyle USMC. As a result, Bianculli notes, “all the Smothers Brothers had to do to build a reputation for topical comic commentary was to say anything at all.”

Many of the controversies seem tame today. For example, there was the CBS affiliate that complained of the “extremely poor taste” of a comedy sketch that revolved around Tom Smothers getting a tablecloth caught in his zipper. Or there was a Jackie Mason routine for a March 1969 episode that helped bring the simmering relationship with CBS executives to a boil. CBS refused to air part of it, feeling the comedian discussed sex in a manner not fitting for prime time television. The offensive joke? “I never see a kid play accountant. Even the kids who want to be lawyers play doctor.”

This was an era where Petula Clark caused an uproar by touching Harry Belafonte’s arm during her television special, the first time a man and woman of different races shared physical contact on national television. Americans didn’t have access to dozens or hundreds of channels to watch or record on different television sets in the home. There were only the three national networks and most families watched shows together on the sole set in a household.

But not all the attention focused on whether material was too risqué. Likewise, it didn’t always take years for change to occur. In September 1967, the Smothers Brothers were the first to bring Pete Seeger, blacklisted in the 1950s, back to national television. Because CBS viewed part of Seeger’s “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” as an attack on President Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam policies, it refused to air the song. When Seeger appeared on the show again five months later, he performed it without objection from CBS.

The more material was cut by CBS, the more intractable Tom Smothers became. When a mock sermon by David Steinberg on an October 1968 episode led to a record number of complaints, CBS instituted a first-ever policy of providing affiliates with a closed-circuit telecast of each episode before it aired so local stations could decide if they were going to carry it. By then, the irresistible force of Tom Smothers and the immovable object that was CBS were wholly antithetical.

The ongoing skirmishes culminated in March 1969 when the show brought Steinberg back with another mock sermon. CBS had had enough. Calling Steinberg’s routine “irreverent and offensive” to the audience, it claimed the Smothers Brothers breached their contract by not timely providing a tape of the episode for the closed-circuit telecast to affiliates. It terminated the show. Although the Smothers Brothers would eventually prevail in a lawsuit against CBS, they almost became, like their show, a piece of television history. The Steinberg episode never aired.

Again, though, controversy is not all that marked the show. It won an Emmy in 1968 for comedy writing. (Tom Smothers left his name off the list for fear it would hurt the other writers’ chances. He belatedly was award that Emmy in 2008.) It spanned the entertainment spectrum. In its first season alone, episodes featured Bette Davis and Buffalo Springfield, Jimmy Durante and The Turtles, and Lana Turner and the Electric Prunes. The show helped launch the careers of Glen Campbell, Mason Williams, Pat Paulsen, Steve Martin and Rob Reiner.

The show also was known for having musical guests before their songs hit the charts. Among those appearing on the show were The Doors, Jefferson Airplane, Simon and Garfunkel, and, in a quite notable performance that would leave Pete Townshend with hearing loss, The Who. There was also a guest appearance by George Harrison and the American premiers of the videos of the Beatles performing “Hey Jude” and “Revolution.”

Relying on extensive interviews and research, Bianculli does a fairly good job detailing all these aspects of the show and their relevance and impact. There is, though, a tendency toward repetition and occasionally causing some chronology confusion. It also suffers the inherent inadequacy of the written word to describe performances appreciated best with sight and sound. Still, given how in-depth Bianculli goes, the book is quite readable.

Dangerously Funny leaves little doubt a short-lived variety show altered the face of television. Somewhat ironically, though, while that show seems tame today, there has yet to be another prime time program on the three major television networks doing what it did more than 40 years ago.

What [the Smothers Brothers] managed to say and do was important, and what they were prevented from saying and doing was not less meaningful.

David Bianculli, Dangerously Funny

|

Disclaimer

Additionally, some links on this blog go to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. There is no additional cost to you. Contact me You can e-mail me at prairieprogressive at gmaildotcom.

|

![]()